The sisters arrive with their father, the bearded pianola instructor, who’s dragged them along. The woman, the client, is not unkind, but not welcoming either. She watches them remove their snowy boots at the door before ushering them inside. She clears her throat. The daughters, she thinks, are ill because they are thin and hunched like old women with holes in their bones. They are holding hands.

The woman lives alone in an apartment with moths she cannot see. While she sips tea, the larvae spin cases around themselves. The woman sighs, imagining windows embroidered in her tablecloth. The larvae drag their cases across her rugs and grow within the yarn naps—lay eggs and eggs. The woman sighs because she feels porous; when she moves, she believes the room passes into her and grows soft, bending into cold spaces. When she rests, she does not want to move again. But now she leads the daughters and the father quickly into a paneled room past a chaise lounge and tall open windows, though it is snowing outside, to the pianola in the corner.

The daughters insert the roll expertly into the spool box. It was their father that taught them after they sloughed the last catalogues of smoke from their skin and rose from the bed, holding hands. The smoke from the Asch Building where they cut rolls of taupe-colored fabric to be sewn into shirtwaists; the smoke in the sealed room where they grew thin, thinner—smoke through which their shears could not sing a kind song. They dove through a window on the ninth floor, through measures of flames. The older daughter bounded first, her fingernails rattling loose when she landed. The second daughter stared into the fire until she felt it in her throat deep black.

The father describes the daughters’ actions at the pianola to the woman, whispering. He doesn’t know why he is whispering, or why he has opened his eyes so wide, but feels that it must be because of the woman. There is ice in his beard. The woman stares at the daughters, nodding. Their movements are small and correct. The paper moves inside the box, clicks. The keys depress and Chopin fills the room. The daughters work together, operating the pedal levers and the tempo control with their fingers. The father says, Pedal. The father says, Pneumatic motor. Exhauster. His beard drips. He tries to catch the drops in his palm. The roll is a transcription of the music, he says. It is not an interpretation, he says. The woman stares at the daughters, nodding.

The older daughter can spot small moth-eaten gaps in the woman’s sweater. If it were somehow fitted into the pianola, it would play a charming, yet forgettable song, the daughter thinks. She will not tell the woman about the holes in the sweater. It is not what she does and it is not what the other daughter does either, or the father. It is their job to instruct new pianola owners how to manipulate the instrument, to breathe life into the songs through the holes in the paper.

The roll completes its course and the music ceases. The woman applauds with tears in her eyes. She turns away. Wind breathes snow into the room. The father says, You can increase the tempo. The father says, Nine feet of paper can be played in one minute. But the daughters hear: nine stories, nine stories. The older daughter recalls the fire murmuring through her sister’s hair. The younger daughter remembers the bins of scrap material and the bins of finished shirtwaists burning with the same intensity. This was significant—but why? In their dreams, the daughters drag themselves across a coverlet of dead women. The women crumble beneath them like a ruined city in a storm.

The daughters rewind the roll. The father encourages the woman to maneuver the levers. Water drips from his beard. It lands on the rug where small moths are thrashing across it, hungrily. The woman pinches the brass levers and moves them when the song begins. She watches the winding perforations in the paper, pulls her hands away from the levers. The music becomes lifeless. The daughters bring the woman’s hands to the pianola. The woman feels vulnerable, and angry that she feels this way, but she has been waiting for someone strong to show her what to do for a long time.

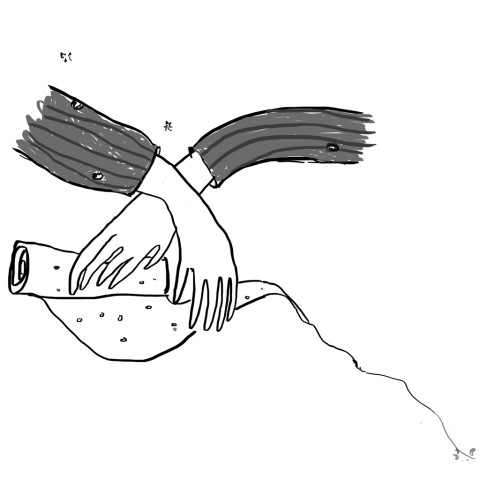

Sometimes at the factory, there is a slip in the gears and the perforations that have been cut into the rolls of paper are not aligned to mimic the music advertised. The rolls are discarded. The father brings them home and the daughters peer through the holes, wonder how the music would sound, and try to perceive the mistakes. They unwind the rolls and draw wild, dancing figures using the holes for the eyes, the mouth, and the heart.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.