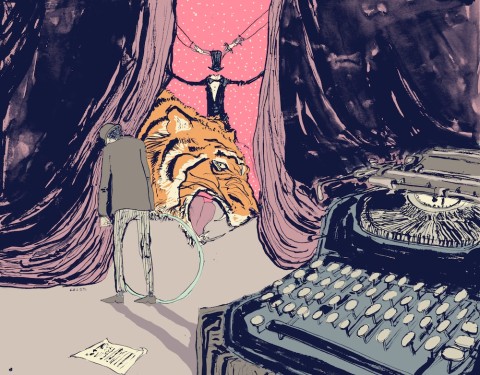

Only one of his fingers he couldn’t use, the baby on the right. He had irrecoverably damaged it one evening in the circus when the tiger trapped his pinky between the height of its arching spine and the hoop. All four other fingers of his right hand were in fine working order, and were working now to punch the keys of the typewriter:

Dear sir—tut tut—Most esteemed sir, your ever obsequious servant requests—nay—begs an interview with his master. Was “master of the circus” too much? Your ever obsequious servant begs of his master (of the circus) a short and private tête-à-tête to discuss, amongst other things, his wanting two specially coloured hoops for the forthcoming spectacular. One, if master should so condescend to acquiesce, looped round and round with gold silk streamers to match servant’s made-to-fit glittering frock coat and shorts, which the dressmaker has at this very moment delivered stitched to perfection. And two—something rather purple I should think to cover the second colourless hoop. Something rather purple to contrast greatly the tiger’s curving spine, hence your able-bodied servant might retain the use of the remainder of his fingers, for future sake. Do not for a second, sir, imagine I mean to be fresh in my requesting the latter. On the contrary, I believe firmly, even devoutly, in the principles on which this circus is founded, a copy of which I carry on my person at all times: To keep the circus animals at their best; To keep the circus performers at their best; To keep the crowds coming back to the circus for more. It is on these principles I’ve staked my life. If ever, sir, I have let the hoop slip in the past, I assure you it is only because, really and only owing to my somewhat limited hand grip, being one finger short per say, and by no stretch a show of disrespect to you or your circus. Your circus has allowed me to stretch my abilities considerably. Not satisfied with being merely a one-hoop-holder, you’ll recall, sir, my ardent training, passionate and vigorous—day and night, day and night— to rise in rank to a two-hoop-holder, a hoop-in-each-hand-holder. And now that I’ve achieved such status as you’ve condescended to bestow upon me, your servant, I request, nay, beg of you two specially coloured hoops, one in gold glitter and the other in deep purple, for the forthcoming spectacular. Lest you should doubt the sincerity of my position, let me forever reassure you of my desperate excitement and hungry fervour for our upcoming, and what is sure to be most stunning, extravaganza. But further still, concerning the circus tiger, if it be so in your power (which I might say that I know it is), if tiger’s teeth could be so blunted with a file, so as to reduce my dancing about on the platform during the performance, thereby diminishing the risk of one’s little finger becoming trapped between…you understand. For what good, sir, frock coat and shorts when tiger’s teeth are coming directly for me? What then do I wish finally to communicate to you? Without going into too much more detail here, I’d like to point out a slight glitch in the running of the show. It has become increasingly difficult, you’ll appreciate, for a man to run away with the circus, when the circus appears to have begun running away with him and all of his— What I mean to say, sir, and never were there two more respectful working hands than those which type these words, but founded exactly on whose princip— I feel under the present circumstances more than ever the limitations of my incapacitated stature, for tiger is no mere household cat, you perceive, nor are the two of us playing hoops together with tiny tambourines—

With that he tore the paper stream from its roll and watched the page float down through the sunlit and dust-kissed afternoon air to the floor. What indeed did he mean to say—the circus running away with him! It’s quite extraordinary, how one gets caught up in and carried away with one’s ideas. Just this morning, for instance, he noticed the slight limp of the trapeze-artist; the small goitre-like lump developing in the throat of the fire-breather; the caked and creased face of the contortionist, her sagging behind. He thought of the pirate peg-leg of the circus announcer, his master, top-hatted mother goose of the carnival. The little deformed man’s starched and scratchy voice ringing in his ears (“Ta da! Ta da!”) as his lame finger traced the cage of the tiger. Up and down, up and down, his pinky slid along the cool gun-metal bars. Over and over again it ran, until cage, bars, tiger, hoops—all ceased to exist for him, and all that remained in his imagination was an idea of the circus, on which he’d based his miserable little existence.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.