The daughter after all—beyond roads, cars, white plain hospitals, and parents: blankets that scratch, the notion of speed, one’s first sensation of a color as being separate from light. Shadows surround her. She buys a yellow t-shirt in a store one day, forty to fifty years from now, and it reminds her of a time eight months ago when she bought a yellow t-shirt in a store. Time is not edgeless, she thinks, despite its best appearances. The daughter is not yours. Everything written is a pataphor for someone else’s coupling.

Doctors, surgical green, sit and chat in a well-lit room as weather stands outside. They are not her parents (they will not name her), though for these moments, in this world, they might be worth mentioning. They bring her home in the rain, they show her rain for the first time. They give her time itself, and that time, too, passes. Procedurally exact ancestors in their capacities for love, people who care and do not care. Home movies taken like coffee breaks with so many images of young frowns or smiles, remembrances of shapes, this infant (still unnamed) held higher by green gloves and learning for the first time how to kiss—not with a boy, but with a neoprene thumb instead—forerunner, already, to a high school experience significantly above average.

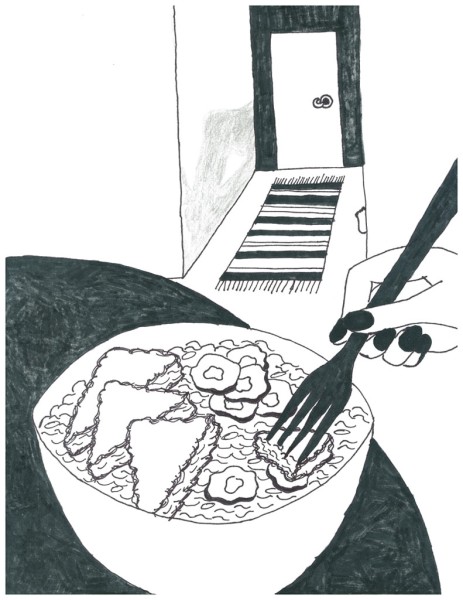

Going home that night, changing into street clothes (bright t-shirt and dark jeans), the high-risk obstetrics nurse working days at a local hospital in White Plains, New York, eats a dish of marinated tempeh over barley and watches her girlfriend shave her legs. In these moments, in this other world, she brims with love for the woman before her. She counts the razor strokes, each stroke a simultaneous blurring and compounding of the one that preceded it. Each stroke tracing somehow its own differences within the pack. They cannot explain it, but this is just something they do together—have always done together—a way of being paired yet also quite separate. Surely, she thinks, they are the daughters of someone. Surely, she thinks, they know what’s going on. She counts the movements of her lover’s shadow projected on the hallway wall beyond the bathroom, she counts up to the mid-twenties and loses interest.

Time does something to a game, to an image: makes it important, makes it unbearable, makes chance inconceivable, makes it grave. She enjoys her life so much, this nurse, and so perfectly—even the sounds of a radio when the weather is unclear.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.