Content warning: Due to the historical themes explored, this story contains trigger warnings for depictions of self-immolation (Sati), violence against women, child marriage, and sexual assault.

5. Sati /ˈsʌtiː/ n. Sati is a former Indian practice, in which a Hindu widow threw herself onto the funeral pyre of her deceased husband, thereby burning herself to death.

4. The last choice the women of her village had to make was how they wanted to swallow their deaths. Mounting their husbands one last time. Or lying back on the firewood, facing the sky, the slits of their eyes honeyed with tears and sunlight, pickled shut.

On her back, beside the corpse, the two of them would burn together, the flames knotting up the pile of teak logs, smoke as thick and sweet and sticky as molasses. But even then, the girl’s hair spills from her head like tar. Fire clings to her first. The pyre louder than anything she’s ever heard, flames snapping and whistling and licking at her like men.

Sometimes this seems like the only choice the women had ever been given. That is the only thing you own, her mother had told her, the only thing they owe you. Your children belong to your husband and your home belongs to the earth and your body belongs to a god. But your death, it is for you to metabolize alone, and your last meal is your own tongue.

3. Because girls like her couldn’t own anything, all her life she’d made up superstitions that she would never speak, keeping them pressed to the inside of her cheek like a piece of candy that would tint her spit sweet that she had to make last a lifetime. She, alone, mother to these thoughts that no one knew of, that no one could take away.

When she was nine and she’d stumbled over a tile that jutted up, popped loose from the ceramic jigsaw, its jagged edge had stamped blood between her toes. Her dish had slipped out of her hand, and the voice of it rattling to the floor, its metallic fluttering, had been the closest thing to music to touch her in two years. She’d kneeled there for a while, her fist clasped around her foot, blood oozing from the cleft. Rice splayed across the floor like light. But the last time she’d heard cymbals had been at her sister’s wedding, and the clang had scraped the bone of her ear the same way. Later, her mother had knelt beside her, raking rice back onto the plate. Five seconds, she’d said, you only have five seconds to react. The pulsing heat of the day had frayed her thin, hunger pooled heavy in her stomach and she’d registered only the words, severed from the incident, the way superstitions wove themselves together. You only had five seconds to unbreak something.

She counts to five. She teethes open ricin pills with her incisors, blows the chalky spittle loose through pursed lips into his tea. For a while the strand clings to her chin, swinging like a locket.

2. On her wedding day, her cousins drape her in satin, pleating her into a bride. She sits between them, cross-legged until her feet begin to buzz with a static that radiates up her ankle. Her mother tugs her hair into a braid, pulling her vision taut, the world ripening tight like the skin of a plum. Flower blooms into flower bleeds into garland melts into girl, into mother.

She hadn’t wanted her wedding to sound like this. She’d wanted the radio music that hung in the air at construction sites, the workers splotched in sand and sweat and bruises as they washed themselves clean of their livelihood at the end of the day. She’d wanted pre-recorded songs that hummed around her cochlea like an insect trying to burrow into a home. Music sugary from the radio, songs smothered with electricity, swaying an inch above the ground like a heatwave.

Instead, the wedding drums and cymbals pound loud enough for all colour to split from its bones like the negative of film. But gold menthols her neck and wrists and ankles white in the rosy heat, anchoring her to consciousness, keeping her from igniting into vapour, keeping her body condensed into a body.

1. She understands now why women wear jewellery ringing all the brittle places their husbands would hold them. When you are kneaded, you must be pliant, her mother had told her. He lies on top of her; his breath pearls onto her collarbone. His presence is something carved out of her, a negative, so hollow that it wants to swallow her.

In a way, women prepare to burn all their lives. Over stoves, their fingers comb through the fire. Splattered oil pockmarks the backs of their palms; their hands blistered into their mothers’. They stoke half-rusted coals with the backs of their nails. Naked, you must be soft. But years of flipping bread over bare fires, and their fingertips have pawed thick into an animal’s.

As a child cooking for the first time, she’d been afraid to bring her hand to break the brick stove’s orbit, afraid it would sear her flesh into meat, salt-cure her tongue into a shrivelled preservable. Her mother had gripped her wrist so hard she couldn’t feel her fingers anymore, hand tourniquetted to anaesthesia. Mother, unworried about the rest of her daughter’s body trying to rip itself away from the arm, had pressed her daughter’s raw fingers against the coal, only for a second, singeing on a scar. Her mother had explained that she’d have burned herself eventually. This way, she didn’t have to be afraid anymore. In another life, she can be afraid of fire.

She crosses her legs, trying to cut off its circulation, amputate herself into defiance, fizzle her legs into froth again. Bare, she is malleable as gold. But her fingertips are charred into a reptile’s. He does not mind that, as long as the rest of her is soft, so that it could be mistaken for the inside of a body.

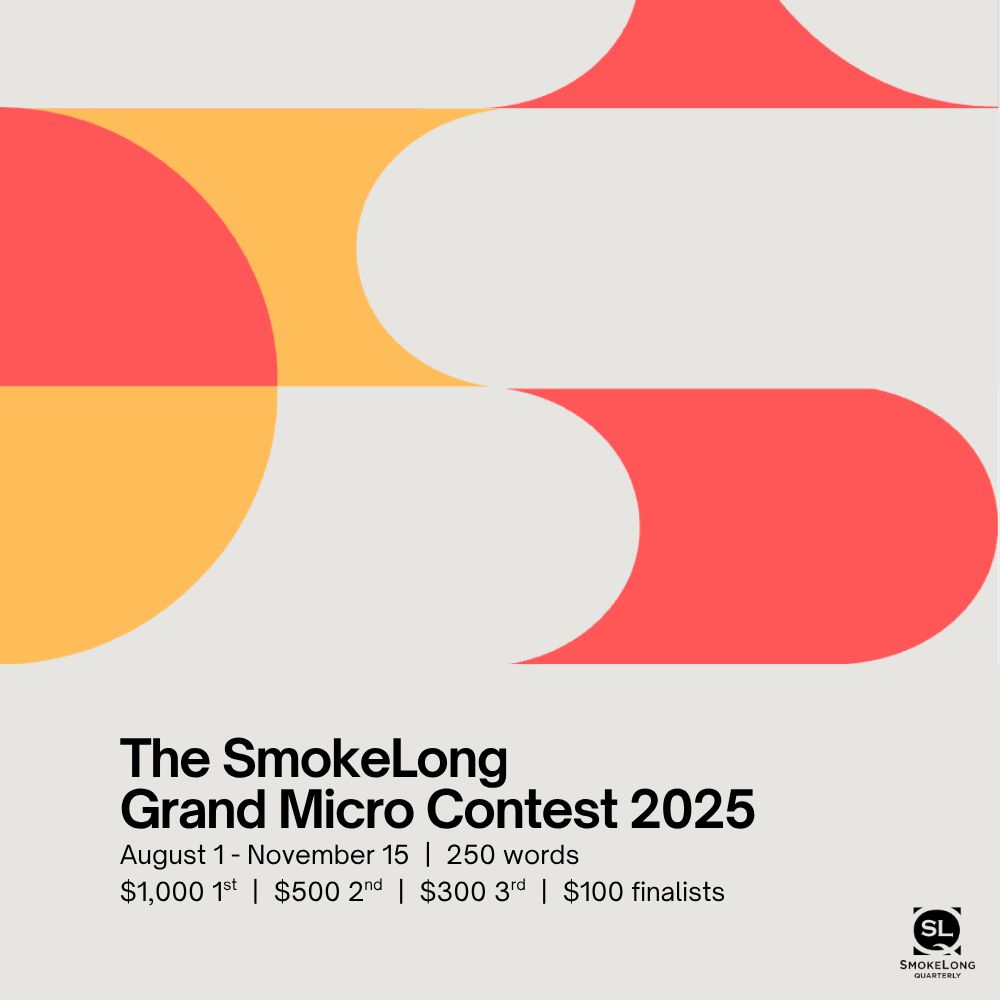

The SmokeLong Grand Micro Contest (The Mikey) is now an annual competition celebrating and compensating the best micro fiction and nonfiction online.

The SmokeLong Grand Micro Contest (The Mikey) is now an annual competition celebrating and compensating the best micro fiction and nonfiction online.