We were with him near the end. At the Natural History Museum, we ogled corpses. We loved how dead they were. Bones of fishes, stuffed penguins, bugs preserved in ethanol. Emma pushed his wheelchair through the first few exhibits, and Tony did the rest. He viewed the creatures through thick spectacles, his eyes fishbowled in their dense glass. The rest of us took photos with cheap cameras, pushing down the button to load the flash, preserving in film what was already preserved in formaldehyde, moving here and there around the wheelchair, ignoring him.

We were allowed to dress however we liked for the fieldtrip, and we had dug through drawers filled with khaki skirts and gray polos to find a hint of green or orange, a pair of jeans worn on the occasional Saturday at the mall. We loved the opportunity to show our style, convinced that choosing the right blouse or t-shirt could change the trajectory of our lives: convince our crushes to finally love us, catch the eye of a modelling agency scout, allow us to finally ascend to the ranks of popularity that we pictured as we lay awake at night.

We knew all sorts of secrets about each other. We watched as Emma kept herself side by side with Patrick in the Saharan Desert exhibit, offering small, awkward jokes as he tried to maneuver away. We watched his eyes as they followed Lillian, who was oblivious, or would be till lunch time, when one of us would surely tell her. We never thought of him as being part of this network of secret desire. He, we figured, was medically exempt from crushes, like he was from PE.

We didn’t like that he had to be wheeled around the museum. We were constantly waiting for him. We would bolt up the stairs then have to stand in the lobby of the next floor as he slowly ascended in the claustrophobic elevator. We would never say anything about it, but we thought it. If he walked around school, why couldn’t he just walk now? A week or so ago he had shown us the hole in his chest where they’d put in the feeding tube during his surgery. Very cool.

Our parents talked about him very sadly at home. What a shame, they’d say. His poor parents. We heard words and we didn’t know what they meant, inventing our own meanings. Marfan Syndrome meant he was very tall. Glaucoma meant he had to sit close to the board in class. Aortic Repair meant they had fixed him. None of this added up to why he couldn’t walk through the museum, or why our parents spoke about him like there was a ghost in our midst.

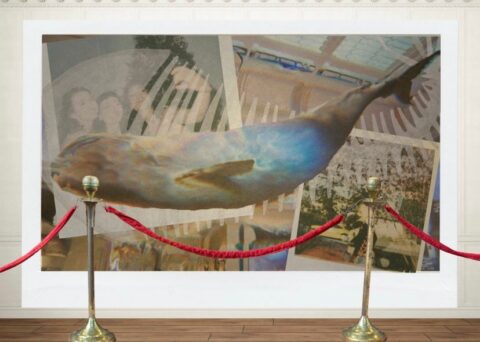

We admired the wide underbelly of a blue whale, suspended from the ceiling. He was looking sleepy. Mrs. Kerwin approached him and asked if he needed anything. She would’ve never done that to the rest of us. She had short red hair. She wasn’t mean but didn’t go out of her way to be kind. He shook his head softly. He said he was fine. He turned up his head slowly to face the whale.

At lunch, we raced to the front of the line, drooling for a slice of pepperoni and the juice box of our choice. The teachers bid us make way, and we parted like Moses’ sea to grant him passage. A canopy of hungry eyes gazed down as he wheeled silently to the front.

At the end, we piled into the school bus, anxious about who would sit next to whom. He rose on shaky legs from the chair, accepted Mrs. Kerwin’s guiding arm as he navigated the few steps up into the body of the vehicle. He sat in the first row, slumped into the seat. Our chatter must have swelled in his ears as he went silent.

That night, a spiderweb of texts delivered the news. Rebecca heard somehow and told Sophie who told Alex who told someone else and so on. Some were told by our parents, some by a friend. We reckoned for the first time with something. We pictured a body found in a room by somebody that loved it. We saw our own selves differently. We looked in the mirror and thought we could break, feared what might break us. We never mentioned that we had always figured he was fine. We never talked about how nobody sat next to him on the bus or how we’d roll our eyes when tasked with pushing him along. Where had we gone wrong? We hoped he thought we were kind. We hoped that he, too, was naïve.

Our parents intensified in their wistfulness. Missing homework went excused for a week or two. Then, the world became normal again. We switched seats in class and there wasn’t a seat anymore that used to be his. We stopped grappling with our own mortality.

Though surely, we’d return to it. At reunions they’d show him, preserved forever in his eighth grade portrait, the flash flattening him against the gray board behind him, like some exhibit we milled past and mentioned politely. We felt in a strange and unidentifiable way, having learned then what it is to live thirteen years, what it is to live twenty or thirty or a hundred years, a buffet of years that we had greedily eaten up, realizing just as it dwindled that we wouldn’t ever be full.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.