Another dating attempt, city park, where a goose—years ago—chased her toddler son, both of them waddling furiously as she laughed. She waits on a swing, carefully, since she’s prone to motion sickness. She has to pee. But not badly.

His station wagon pulls into the gravel lot, this psychology professor she met at a bar. Crunch of rock and tire. She stands to wave and a child darts for her swing.

“Hello there,” he calls, shutting the driver’s door then opening the back. She imagines a tartan blanket, a plastic sack full of ripe apples, a well-chilled bottle of wine to celebrate the turning leaves.

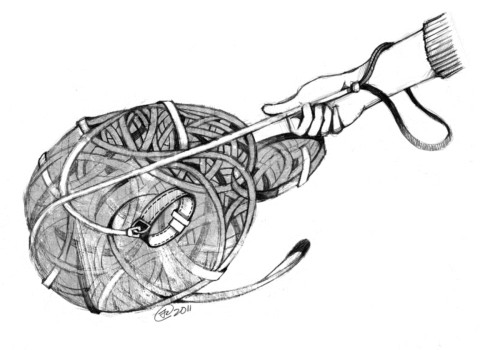

Instead, he gently brings forward into the afternoon sun a stiff, wire leash attached to nothing. An empty collar.

“It’s okay, girl,” he says in a tender, bedroom voice. “It’s just a park. You be a good girl for daddy.” He flicks his wrist, and the leash bobbles and surges towards her as if a lively puppy danced there.

“She likes you,” he says. “She’s usually quite shy. Meet my Trixie Jean.”

She remembers how he snapped the peanuts in the bar and dug out the meat without taking his eyes from hers, how he flicked the shells to the floor so purposefully. How she’d liked that. She looks down, through the empty collar, at the taupe dirt where a beetle pauses.

“Hi Trixie Jean.” The beetle scrambles under a stick, and the collar—baby blue, studded with rhinestones that spray rainbows at her feet—seems to wink at her. He waits, as if she’s supposed to reach down and scratch behind the ears, pat the invisible rump, gurgle whatagoodgirl-yes-whatagoodgirl. She says, “Should we all take a walk on the river trail?” She keeps her eyes on him, the smile she’d found so instantly attractive; she watches the tiny gap between his bottom teeth expand when he says yes.

On the trail, they barely speak. The wind weaves the sun through the trees, and it’s as if a thousand black and gold butterflies rise and land in the leaves every second. She wants to tell him this, but he is watching the dog collar wiggle through a hole in a tree. Chuckling.

“What made you decide to get a dog?” she asks. Trying.

“The same reasons anyone gets a dog.”

“Which are?”

His wrist falls slack, the collar dips to earth. He says, briskly, “I like the companionship.” A chipmunk springs past them, but the collar shows no interest.

“Why Trixie Jean?” She persists, waiting for revelation.

He shrugs. “I almost called her Shadow. She follows me everywhere, and her coat’s a lovely, deep gray. Don’t you think?” He holds the leash out so it trembles. The collar keeps winking: play along, play along, this is only a game.

“When I was depressed once,” she says, “I mean real depression, I called it the black dog. I didn’t invent it, someone famous did. But my son drowned in a boating accident, and that was how I felt—like a big, black dog was watching me. Like it would never stop stalking and never attack.”

She takes a slow breath, and the collar suddenly jumps and strays over to a bush. He says, “The right drugs can make all the difference.” Then, “Bad girl!” For a moment it seems he means her, but he is speaking to the collar as it strains to follow something into the undergrowth. How, she wonders, is he sure the dog hasn’t already slipped away? The cords of his wrist flex and twist. The wire leash is so stiff that he could never hold his invisible dog in his arms, not with the collar on, never close the way you must hold what you love.

“It was a long time ago,” she says. “I really have to pee now.”

She hopes they will head back, but he hands her a crumpled tissue from his pocket. “We won’t watch.”

The professor and his collar wander toward the river. She wants to cry, “Watch! You must always watch,” but they’ve vanished. She squats in the dirt alone, and relieves the pressure. She remembers how in third grade they’d traced and cut out life-size human bodies, how she’d been teased for pinning the paper bladder between the lungs. But it makes sense to her now. The fill and leak. Fill and leak.

The wind kicks up, and as she buttons her pants, she stares up where the sky plays hide-n-seek between leaves, where the sun butterflies dance in the treetops until the wind collapses. Somewhere by the river a child shouts.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.