“Unexpected gifts,” whispers the plump nurse whose name I’ve forgotten. “That’s what remissions are.”

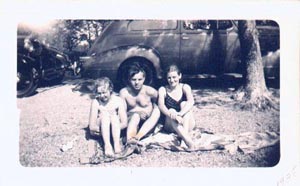

From beneath his pillow, my father takes a photograph. It’s black and white, small and square, the edges deckled in crisp half-moons. He taps the gloss image with his tough fingernail. “That’s me,” he says, showing it, “me and Betty Lowe.”

It’s Mom and Dad all right, so young in swimsuits.

He lies back on his bed. “I was twenty-two, Betty seventeen. We picnicked, down on the river.”

“You remember?”

The nurse pokes me. ‘Don’t spook the gift,’ she seems to mean.

The doctor warned, of course, that there’d be lucid days. “Keep your hopes in check,” he reminds me again, clicking his pen like some code. “These brief remissions aren’t significant in the longer view of things.” He pockets the pen as he leaves.

“Everyone’s gone now who cares,” my father says. “Once I’m gone, it’ll be like it never happened.” There was more life in his eyes, more animation in his face than I’d seen in a very long time, and coherence to his words.

“I’ll remember,” I say. “I’ll care.”

“My son’s a writer,” he tells the nurse as if I’m not there. “He can imagine anything, make it up from nothing and care like it was real.”

I turn away, scolded and shamed, still his boy at fifty-six.

“Here’s a tablet,” she says to me, “a felt-tipped pen.”

I take them and a tissue that she offers, too. There’s an Indian on the tablet cover, a chief in full headdress. Inside, the paper is pale like old skin. The lines are the color of veins.

“Write this down,” my father tells me, pointing. “All of it.”

I uncap the pen, touch nib to paper. “A perfect day,” I write, knowing that’s how he’ll begin.

“A perfect day,” he says, “the river high on its banks. Chill water laps our ankles. Beneath our feet, river rocks are slippery with moss. There’s a muddy smell to the breeze, and shore weeds make riffle sounds like pennants in stiff wind. Downriver, a paddle wheeler puffs out clouds of steam, its whistle shrill, louder than any toy.”

I look over when he pauses. It’s so good to see his face alive like this. As he starts up again, my breath catches high in my chest. It’s all I can do to go back to writing.

“Betty’s beside me, on the plaid blanket we’ve spread—three blankets, three couples, my box camera passed around. A Victrola somewhere plays music, Skinny Ennis singing ‘Too Many Tears.’ Overhead, split-tail martins fly cursively. We try to read their penmanship, decipher what they write on the undersides of clouds. Betty traces their paths with a weed stem she’s plucked. ‘Maybe,’ she whispers close to my ear, ‘they’re writing infinities.’”

“Wait,” I say, scrawling fast now. “Infinities?”

My father’s eyes find me. “Like eights,” he says. “Just write.”

“Just write,” the nurse says, too.

The old man sits straighter now in bed, propped on an elbow. “Betty tells me, ‘Infinity means forever in Algebra. Enormous. More than you can ever know.’”

I draw the symbol on my pad and he nods.

“I like that she’s smart,” he says, “don’t get me wrong. But more it’s how it feels right then, me beside her. Even before I touch her, I know how her skin will feel. And even before we kiss that first time, I know it’ll be like something we’ve always done.”

“I can’t write that,” I tell him. “It’s sentimental slop.”

“It’s true.”

“True don’t count for shit,” I say. “Give me specifics to write, not conceptual crap.”

“Specifics?”

“Like the river stuff. That was good. Only this time about Mom.”

“Okay.” He’s on his back now, not looking at the photo anymore. He watches the ceiling like a movie screen. “Auburn hair scrolled up on both sides. Ribbon-tied, a wisp loose at her neck. Her face is all soft curves. Not a straight angle anywhere, except the ridge of her nose. And freckles, God, a mask of freckles—pale so you only notice up close—under her eyes, across that gorgeous nose. Soft shoulders beneath her swimsuit straps. And her pulse like a metronome in the hollow of her neck. The rise and fall of her breathing is God’s own lullaby.”

It’s the nurse who interrupts this time. “You miss Betty,” she says. It seems obvious to me.

“Every day.” He seems weary. “She died young. A quick cancer. Summer of fifty-five.”

“I miss her.” I write it, say it out loud, and write it again and again.

The nurse comes close. Her smell is dry talcum. “You were…what? Six?”

“Six,” I say. “I remember, though. Even more, I remember this photograph, the way my father brightened each time he brought it out. He needed me to know about that day, to care, to not let the memory die.”

The nurse sits beside me on the bed. A slipper dangles from my toe, dangles but doesn’t fall. “Can you remember,” she asks, “the last time your father took that photo out and told about that day?”

It feels like a trick, this question. I know two answers, either one right. Both right. “Just now,” I start to say. I slide the photo back under my pillow. “And nineteen-seventy-two, October second, the day before he died.”

“Lie back now on your bed,” the nurse tells me. She eases the tablet from my hand. “We’ll write more tomorrow.”

“Don’t let her,” Father seems to whisper.

I grab it back.

“Write me alive,” he says. “Write me confused in this hospital, rambling. Write a plump nurse at my bedside. Write that day down, son. Keep it alive, the river smell, the tattered blanket we spread, my Betty beside me, the stem of her weed tracing martin flights.”

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.