On the idea of contour as scalpel for creation and self-flagellation: The narrator eliminates the father’s aesthetic and creates something other. Do they create their full self or only who the father wasn’t?

The makeup ritual is both self-flagellation and self-creation because those can be the same gesture. The narrator disciplines oneself (the son) to birth another (the drag queen). It’s violent work of daily erasure and reconstruction, but becoming yourself sometimes requires destroying what you were.

But, also, the narrator isn’t trying to become someone else entirely. They’re carving possibility from inherited material. The narrator sees this other self as both negation (everything the father isn’t) and affirmation (everything they might become). Because looking like yourself, when yourself is unwanted inheritance, is a kind of death—or its reminder.

There are tangible markers (scars, colonoscopy bag, blood, makeup), that seem to represent emotional layers (the scars we carry, the pain and waste, the masks we inhabit). How intentional was the language to that effect? How much of it added in revision?

Mostly intuitive, but I’ve always been fascinated with medical aesthetics—Rick Owens’ splint boots, Hussein Chalayan’s surgical corsets. There’s something so striking about refashioning medical necessity into something worn rather than prescribed.

I had surgery in elementary school and remember the drainage bag attached to my abdomen like an alien portal—this garment that kept me from reaching into another dimension of myself. I am also fascinated by the medical applications of corsetry, how it displaces organs. Drag queens often perform beyond their bodies—cinching waists, tucking genitals—all these ways we modify flesh to achieve a desired silhouette. Like surgery. When the narrator thinks about their corset while looking at his bag, they’re recognizing kinship in modification.

Initially, I read the story on my phone and misread “Her foreignness flared against their whiteness like a struck match” as “… flared against their whiteness like a stretch mark.” It was an interesting misread. Once I reread, I wondered if there was a layer referencing the child as being the reason/the spark (or think they are, as children might) for complications in the relationship and if the narrator identified/related and/or felt co-responsible for the divorce?

Your misreading is brilliant! That’s absolutely there: the child as permanent marking on the family’s (white) skin. Somewhat unrelated, but my mother worked as a home health aide, and I’d join her to visit patients’ homes. I’d feed their pets, tend gardens, look through photographs—not too different from the narrator’s museum tour of the veteran’s home.

Like me, the narrator felt recognition more than guilt. A recognition of something latent, primitive—some ribbon connecting our ungovernable subconscious to others’ externalized wounds, which aches to run our fingers over. They see the photograph and understand themselves as another kind of foreign object in white family structures. Not just the veteran’s family, but the larger American order governing Vietnamese diasporic existence—even as queerness is ungovernable. All that violence to get Vietnamese Americans where we are today—how does it not haunt everything? Not to mention how Vietnamese femininity had been articulated in Western conception: as subordinate to the white masculinity.

The narrator recognizes the particular burden of being the thing that doesn’t fit, that makes other people’s lives more complicated simply by existing. That recognition creates intimacy across difference.

You have this knack for giving us strokes of scenario with very few words (a wonderful mastery of craft for flash). Your places feel so distinctive and visually interesting— cinematic. Do you see things as you write? Or do you construct scenario afterwards?

Thank you so much! This was my second-ever attempt at flash—the first was four years ago, in ninth grade—so I don’t necessarily have a sustained philosophy of setting just yet. I do feel that necessity is the mother of setting: I start with voice and let the world emerge as needed. I think this makes spaces more vivid because they’re functional and do precise psychological work.

I took a class with Timothy Morton my first semester at Rice. They taught that the poem itself is a hallucination, something that exists in the mind rather than on the page. Setting works similarly for me. It’s about giving readers just enough stimuli to register the sensation of a certain orientation, the way a body’s situated in space. The goal is letting readers feel the ledge of something without identifying every surface. Experiencing space through a particular consciousness, seeing only what that consciousness needs you to see.

I love how you used the concept of trust. The narrator goes to the veteran’s home alone. There is a moment, close to the end, when we are privy to the fact that they are not oblivious to the potential danger. And yet, it is the veteran’s trust that is highlighted. There is a vulnerability in being seen and touched: a vulnerability the narrator hasn’t allowed themselves. “As if my mouth were the dangerous part.” What then, to the narrator, might be the “dangerous part?”

The power dynamics are deliberately unstable. The veteran has obvious advantages—military training, home turf. But he’s also being transformed and made vulnerable. The narrator’s mouth being “the dangerous part” comes from understanding that language negotiates and destroys illusion. In drag, voice often betrays the construct—why so many performances are lip-synced. But more than that, the narrator could speak truths that would shatter the veteran’s fantasy. And vice versa. The truly dangerous part is their capacity to witness. To be truly seen, especially in our most desperate moments of becoming—our living gestation—terrifies.

Trixie Mattel once shared this anecdote about doing makeup for a married crossdresser who told her, “You’re so young. You’re so lucky. You can live your whole life as you are.” This always haunted me. The tragedy of existing in the world as everything but what you feel you are. It is exactly what I sought to capture and perhaps expel from myself.

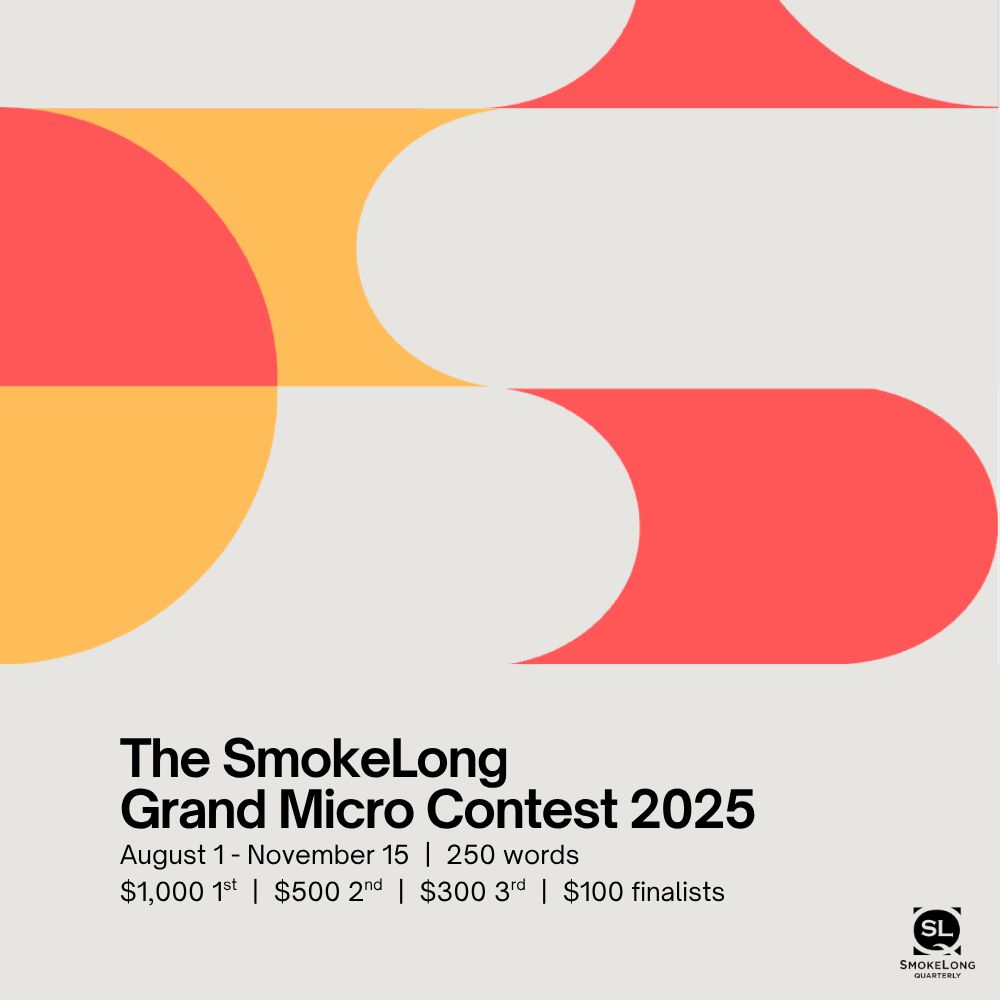

The SmokeLong Grand Micro Contest (The Mikey) is now an annual competition celebrating and compensating the best micro fiction and nonfiction online.

The SmokeLong Grand Micro Contest (The Mikey) is now an annual competition celebrating and compensating the best micro fiction and nonfiction online.