Reviewed by Amanda Krupman

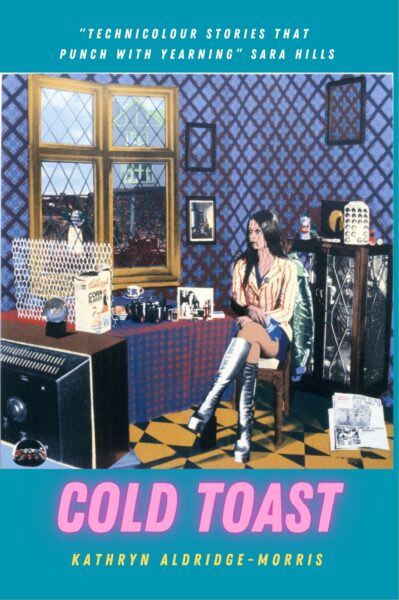

Kathryn Aldridge-Morris’s flash collection Cold Toast [Dahlia Books, October 2025] opens with an ekphrastic story referencing its cover art by Irish printmaker Tim Mara. It’s a fitting beginning, as each of the twenty-nine stories invites the reader to let their mind’s eye wander over details—to absorb the gravity of each domestic object, to grasp onto each time-encapsulated ephemerid (the burnt-orange sofa, the Speaking Clock, Hamlet cigars, Hawaii Five-O) orbiting each protagonist. Said protagonists are all girls and women, and the men in their lives are present and absent at once: The men inflict damage, but they are also somehow weightless. There are fathers and boyfriends—but possibly only one father, one boyfriend. This is, to be clear, a function, not a flaw of the storytelling. While the title story may read like The Feminine Mystique boiled down and poured into a Jello mold, Cold Toast consistently centers complex characters, with plotting and narration that engage and undermine expectations.

While most of Cold Toast’s stories were published individually, there is a central through-line, which makes this collection read like a novel-in-stories. The strongest stories highlight a strength of flash—stories that build on a central image and manifest waves of resonance. As a whole, the collection vibrates with the cumulating magnitude of such images. In “Hotlines,” a ten-year-old girl calls the Dial-a-Ripper hotline from a red telephone box, and, later, when calls ring her home with no voice on the other line, imagines it’s the same Yorkshire Ripper. Her mother knows otherwise. Later, in “Perpetual War: 1983,” a child reads 1984 and imagines Big Brother in mysterious moments she observes in and around her home:

I saw Big Brother in the Ford Catina that would pull up outside our house at night, keep the engine running, watching. I heard Big Brother on the end of the phone, me stretching the yellow coiled wire, wrapping it round and round my fingers, listening to a black and white breath. I started to notice how it was only me and Mum who got the calls from Big Brother.

In the story that follows, “Dinner Party Classic Recipe (From ‘Cooking For You’),” the point of view shifts to second-person, instructing a woman we can imagine is the mother from the stories that came before.

- Remove colleague—dabbing her eyes with her kaftan sleeve, as your husband flirts with your best friend—and place in preheated lavatory, spacing yourselves well apart.

- Carefully spoon out your words: Stop. The. Calls.

Cold Toast’s stories advance chronologically from the 1970s and ‘80s through to the ‘90s, when the child or children voicing the earlier stories have grown, potentially into the adult narrators of the latter stories, who describe watching their parents age and navigating cloaked conversations with them—still piecing together clues and trying to make sense of them. Other stories weave in new mysteries through the messiness and threats of adult life, including lingering exes, MRI scans, and questions such as, “Might we need to enter the witness relocation program?” In this latter section, I particularly enjoyed the elegant, meta dad-joke story of “Elephant,” which is set in a dying father’s hospital room and begins, “The week we learn our father is dying, we bring our elephants to the ward. No metaphors or flowers, says the nurse,” and ends: “Some people say it’s selfish to bring elephants to a dying person’s bedside. They are probably right. But you tell me. What do you do with an elephant in a hospital?” A fair question—and one that echoes thematic concerns woven throughout the book.

Kathryn Aldridge-Morris’s first flash collection is a punchy and cohesive delight for the senses, peppered with dark wit. Its stories of British childhood in the late 20th century toe the line between nostalgic recollection and intrusive memories. Appropriately, the book ends with “The Story You’ll Never Tell,” an unsettling, unresolved tale that is “boxed and buried,” but comes out “in fragments now and again”–which could easily be a description for the pieces that precede it. In Cold Toast, Aldridge-Morris’s stories emerge in hyperfocus and, long after they close, linger.

You can purchase Cold Toast through Dahlia Books, available now.

___________________________

Amanda Krupman’s stories and essays have appeared in a number of literary journals and magazines, with an essay published in TriQuarterly nominated for Best of the Net 2024. She was the recipient of a Jerome Foundation Emerging Artist Award in 2017 and earned an MFA from the New School.

Amanda Krupman’s stories and essays have appeared in a number of literary journals and magazines, with an essay published in TriQuarterly nominated for Best of the Net 2024. She was the recipient of a Jerome Foundation Emerging Artist Award in 2017 and earned an MFA from the New School.

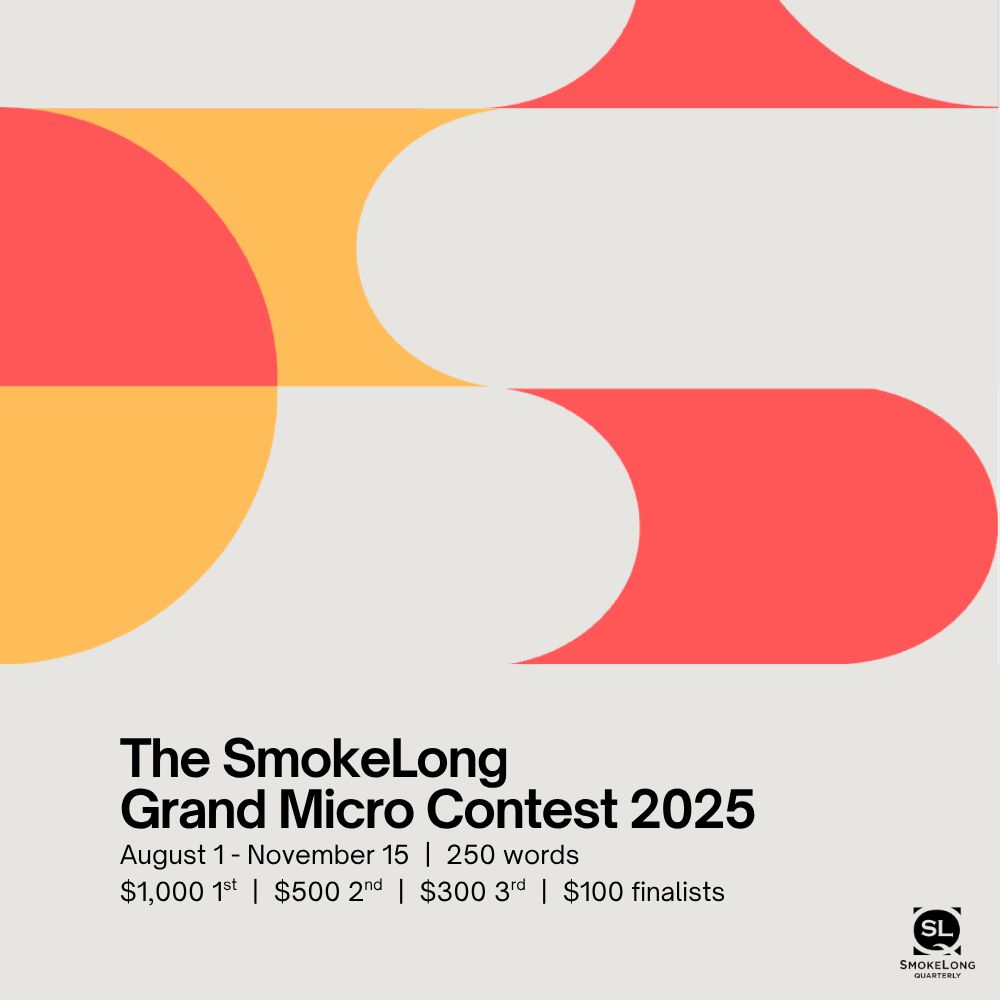

The SmokeLong Grand Micro Contest (The Mikey) is now an annual competition celebrating and compensating the best micro fiction and nonfiction online.

The SmokeLong Grand Micro Contest (The Mikey) is now an annual competition celebrating and compensating the best micro fiction and nonfiction online.