Interviewed by Erin Vachon

Erin Vachon: I had the privilege of reviewing your debut collection, Bare Ana and Other Stories [Regal House, 2025], so this is a pleasure. As a longtime editor of the Sudden and Flash Fiction series, you spent years foregrounding your editorial work before releasing your debut collection. Did anything about this side of the publishing process surprise you?

Robert Shapard: I’m not sure it’s a surprise, but I’m happy people are actually reading my stories. I’m not used to getting feedback. It’s like notes in bottles cast out to sea, publishing stories in small journals over the years. But a collection gets attention all at once, it seems, from editors, blurbers, reviewers, zoomers, bookstore readers. It’s like the notes all washed up on the same shore and people are reading them together and asking how do these relate? What do they mean? They’re finding things in the stories I didn’t know were there. Most of my stories are recent but there are a few older ones that seem different now in a new context, so it’s like I’m discovering myself. That’s a surprise.

You write lovers of all kinds. Married couples, near divorce. New lovers, rekindling their three-date relationship from college. While you explore many relationships in your collection, did you ever think of Bare Ana and Other Stories as a book of love stories?

I did, but not before I started gathering them. I wanted the stories in Bare Ana to be flash length so I was only looking at length. But when I began to arrange them it came to me, Are these love stories? Only a minority of the stories were about couples. Love or lovers weren’t the inspiration for any of the stories. They’re not about love. They’re about pre-natal tattoos, a young girl’s gymnastic performance, a movie monster in a late-night L.A. diner, a science class on how life on Earth was formed. I couldn’t think what to say about love stories, so the idea kept falling away, but coming back like a gentle tide. So let me try to nail it down now: If I write a story about aliens from outer space landing in a city park, I might add a human couple on a bench just to observe them, and then the story might end up less about aliens than the couple.

Your flash are deeply character-driven. Do you often start with your characters when writing stories, or do you approach from a different angle?

I do usually start with characters. They say actions don’t make a story. The story is the effect those actions have on a character. So when I write a flash I guess I go right to the heart of it. If we’re talking about the initial idea for a story, of course any thing or cluster of things can prompt one—an image, a memory, maybe a factoid I saw online. It’s when I think of who would care about that factoid, that’s when the story starts. And it doesn’t stop there. After a few or many drafts the character and the narrative voice (no matter how personal, or distant) become one. So for me every story starts with character even if it begins, “On a windy November day …”

I read that your grandfather was an amateur parapsychologist – strangely, so was mine. Have ghosts and the mystical informed your storytelling?

Maybe the mystical, though I don’t think about it. “Julie Elmore” takes place in a summer school class where we see how ordinary things came together to create life on Earth eons ago. It’s just hard-headed science. But to me there’s something spiritual about it. Maybe the ancient peoples were right: there’s a spirit in everything. And a few of my stories do end in visions. In “Lobster” a woman frozen by an impossible choice sees grasses swaying among autumn sand dunes and thinks how beautiful life is, and in “Aperçus” another young woman tries to save her fiancé, who in her mind is being swept away by a raging flood past downtown Dallas.

As for ghosts, my parapsychologist grandfather believed in them but dismissed them. He told us kids it was okay to be brave because ghosts never hurt anybody. We asked him if a ghost showed up would he try to talk to it, interview it for research purposes. But he said real ghosts, unlike the ones in scary tales, movies, and Shakespeare, have never been known to talk. That was so disappointing! Maybe that’s why, like him, I’ve dismissed them in my writing.

“Aperçus” is one of my favorites, a tender romance about new lovers. You borrow French psychologist Émile Coué’s aperçus, the cosmic awareness captured by stating out loud, “This is the meaning of my life.” How do you find the aperçus in your flash?

I never thought of this—what an interesting question. I do know how I found the aperçu in one story, “Thomas and Charlie.” It begins with a mother, father, and young son consulting a map while driving in Mexico. (I’ll skip the details—dramatic events happen and they drive on.) The problem was I couldn’t find a good way to end the story. I tried some striking images but none of them worked. So in desperation I read and re-read until I found what I wanted. It was the mother holding the map, saying “We’re lost.” That resonated. So I made the story come full circle like a good college essay, adding a new last line: “I understood only that my mother and father were lost.” But it was a far larger “lost” than the one in the beginning, more than this little family. It’s about everything in the story, about wars and love and how far our humanity extends; how a boy’s life is changed; and I guess how poor maps are sometimes. I looked for the aperçu in another story, “Sundress,” and immediately found it, just by keeping that phrase in mind, the meaning of my life. It was a young girl’s unthinking reaction to something that forever casts her destiny. My guess is there are lots of aperçus in your fiction if you look for them.

You’ve said you grew up in a Texan house full of stories. I’m especially struck by the work your stories undertake on U.S. borders and violence, particularly “Thomas and Charlie” and “At the Back Door.” What role does Texas hold in your stories?

Joyce Carol Oates said you have all the experience you need to be a writer by the time you are five years old. When I think of Texas I don’t think of borders or violence but summer evenings when I was growing up, that scree byoin-ing sound of the back screen door spring before it slapped closed. The people I loved and who loved me. Getting up the nerve in junior high to ask a girl for a date, calling on the only telephone in our big old house, downstairs in an alcove near the kitchen, the wall line just long enough to reach the food closet where you could have a private conversation, unless your cousins kept banging on the door, dinner’s almost ready, your mom says wash your hands.

Do you have a favorite flash that has stuck with you as an editor over the years?

Many, many favorites. I’ll narrow it down by picking a favorite anthology, Flash Fiction International. Some of my favorites there are “Idolatry” by Sherman Alexie, “The Extravagant Behavior of the Naked Woman” by Josefina Estrada, “Please Hold Me the Forgotten Way” by H.J. Shepard, “Aglaglagl” by Bruce Holland Rogers, and “Barnes” by Edmundo Paz Soldán.

What about the flash genre first enticed you—and why does it still?

I was writing longer stories, which can take a long time to build to something, and I liked the way flash could do it in a page. Flash didn’t have a name yet, when James Thomas and I started collecting them. They weren’t easy to find, and we weren’t even sure they were fiction. It was the age of experiment. Revolution was in the air. All that was exciting and made us want to find and read more and more. It still does because there are brilliant new and developing writers and flash keeps changing.

What are you reading now?

I just put down a stack of flash fictions I read as guest editor for the Best Small Fictions 2025. It’s their 10th anniversary issue, 110 stories, mostly from the U.S. and Commonwealth but elsewhere around the world, too. I spotlighted 10 in the introduction. It will be published this fall. I read novels, too, recently Tana French’s latest. I am also writing a novel and sometimes pull books off the shelf to look at techniques, like how a certain writer opens his chapters. Re-reading Toni Morrison this morning I realized she would have been a great flash fiction writer.

___________________________

Robert Shapard is known for co-creating the Sudden and Flash Fiction anthologies that had a groundbreaking effect on American short fiction. Now his own stories appear together for the first time in Bare Ana and Other Stories. His fiction has been published in journals such as New England Review, Necessary Fiction, New World Writing, Juked, Bending Genres, SmokeLong Quarterly, Fractured Lit, and Kenyon Review, and has won awards from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center, and the Community of Literary Magazines and Presses. He lives in Austin, Texas.

Robert Shapard is known for co-creating the Sudden and Flash Fiction anthologies that had a groundbreaking effect on American short fiction. Now his own stories appear together for the first time in Bare Ana and Other Stories. His fiction has been published in journals such as New England Review, Necessary Fiction, New World Writing, Juked, Bending Genres, SmokeLong Quarterly, Fractured Lit, and Kenyon Review, and has won awards from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center, and the Community of Literary Magazines and Presses. He lives in Austin, Texas.

Erin Vachon is Senior Reviews Editor at SmokeLong Quarterly, the Multigenre Reviewer-at-Large for The Rumpus, the Multigenre + Chapbook Editor for Split/Lip Press, and an Editorial Panelist for Sarabande’s 2025 Mary McCarthy Prize in Short Fiction. Their work appears in SmokeLong Quarterly, Black Warrior Review, DIAGRAM, Hayden’s Ferry Review, The Pinch, Brevity, The Anarchist Review of Books, and more. Their writing has been selected for the Wigleaf Top 50 and nominated for the Pushcart Prize, Best Small Fictions, Best of Net, and Best Microfictions. Erin writes and edits outside Providence, RI.

Erin Vachon is Senior Reviews Editor at SmokeLong Quarterly, the Multigenre Reviewer-at-Large for The Rumpus, the Multigenre + Chapbook Editor for Split/Lip Press, and an Editorial Panelist for Sarabande’s 2025 Mary McCarthy Prize in Short Fiction. Their work appears in SmokeLong Quarterly, Black Warrior Review, DIAGRAM, Hayden’s Ferry Review, The Pinch, Brevity, The Anarchist Review of Books, and more. Their writing has been selected for the Wigleaf Top 50 and nominated for the Pushcart Prize, Best Small Fictions, Best of Net, and Best Microfictions. Erin writes and edits outside Providence, RI.

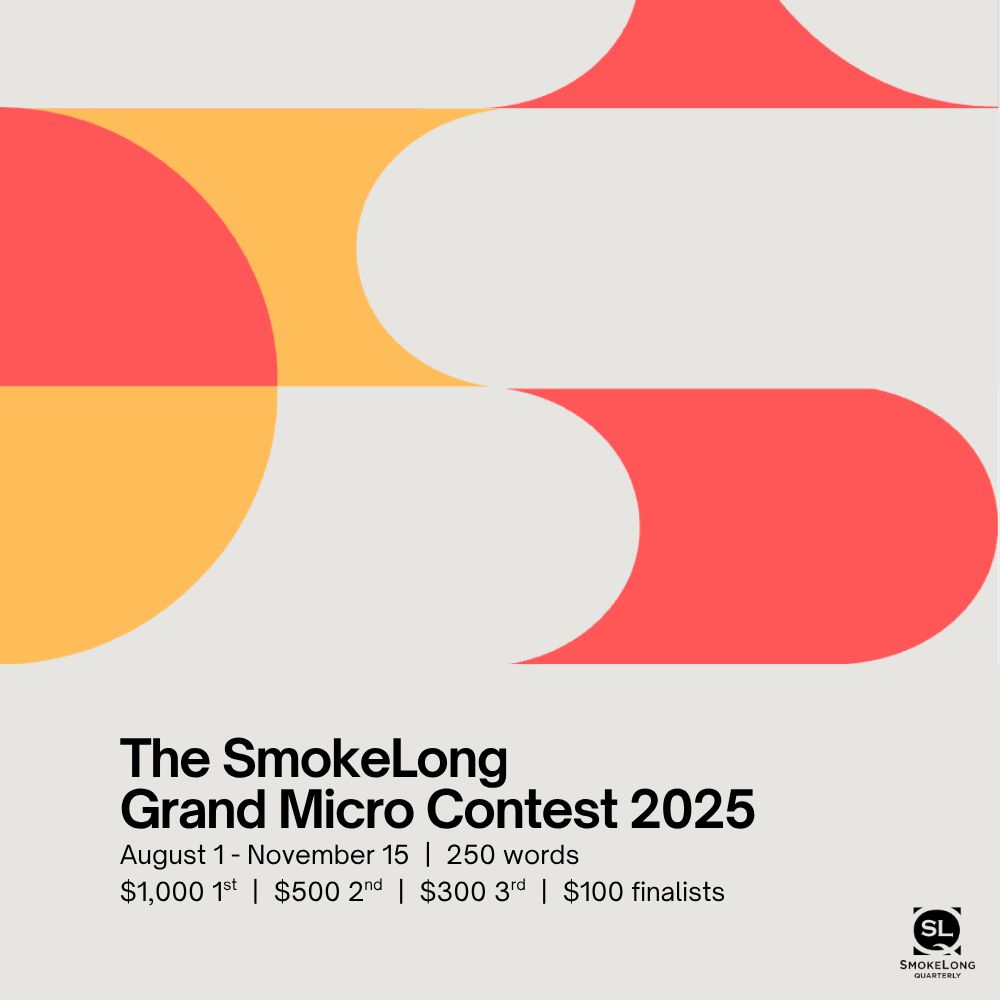

The SmokeLong Grand Micro Contest (The Mikey) is now an annual competition celebrating and compensating the best micro fiction and nonfiction online.

The SmokeLong Grand Micro Contest (The Mikey) is now an annual competition celebrating and compensating the best micro fiction and nonfiction online.