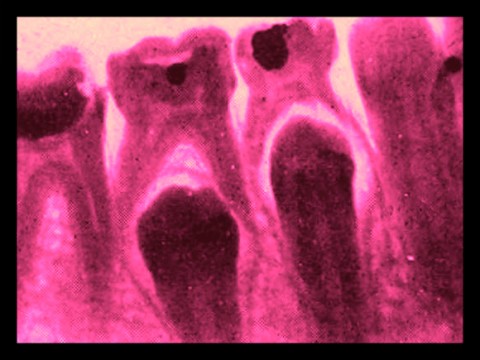

My mother cries in the bedroom where I lie after the accident, “You had perfect teeth. Such perfect, perfect teeth.” I spread my lips and I’m a Jack-O-Lantern, and if I tap the one in the middle with my tongue accidentally I am electrocuted by pain, the locus in the meat of my jaw but it spreads everywhere. I passed out from it that first night when cold ice cream, rocky road, slid over the exposed nerve.

I am ten when the accident happens and so I fall deeply in love with my dentist. We spend a lot of time together working on my teeth—cementing, rebuilding. He is healthy and kind, minty breath, red hair, blue eyes—they wrinkle at the corners above the white mask he wears, and that’s how I can tell when I’ve said something cute and made him smile, hidden beneath the mask, which is all I want to do, it’s all I think about at these visits, as his white-gloved finger swishes against my tongue, pressing it down for a better angle, his mirror pointed at the undersides of my front teeth. “I’ll be right back, sweetheart,” he says, “Don’t move,” laying a heavy lead blanket over my whole body, arranging it gently over my arms and hands, protecting me. He gives me a lollipop when he comes back, I suck it very, very carefully, and sit in the waiting room while he talks to my mother. I’m too old to play with the building blocks, primary colors glowing in the sunlight through the window. I am a very mature, very brave little girl, everyone keeps telling me, my mother’s friends and my fifth grade teacher and assorted dental hygienists.

I am sent to an orthodontist when my dentist is done capping the teeth that can be capped, because I need oral surgery. The orthodontist bores me, I’m not in love with her, with her gray streak, her hands empty of lollipops, only able to rustle up a sticker for my trouble. She tests my teeth, first heat then cold, pressed on the nerve, and the pain makes me faint again, reclined safe in the chair. The root canal takes an hour and half. My mouth feels like a stranger to my tongue when they’re done, but it doesn’t hurt anymore.

Eleven years pass and I see my dentist at a St. Patrick’s Day festival in Poughkeepsie, near the Metro-North by the river. I recognize him, I tap his shoulder and introduce myself, he can’t believe I have become me, that I grew up. “How did this happen?” he keeps saying, sloshing Guinness out of a plastic cup. I show him his good work, opening my mouth and bending my face forward—the caps on my teeth should have popped off six years ago, but they didn’t, except for the one to the right of the root canal, I was getting high in my boyfriend’s dorm in college and I smacked the bowl, the dizzy-colored bowl, green and purple and black, against my teeth accidentally. That one had to be re-cemented. My boyfriend is here, there are so many people between us now, I can see just a sliver of his face: chin, nose, as he leans against the bar, trying to get us drinks. His hand is tapping on the wood of the bar, sliced from his body in my vision by the protrusive stomach of a bald man in a kilt. My dentist examines me, looks like he might put his finger in my mouth again, rub it reflexively along the ridges of my gums. He’s going to die very soon from cancer, but neither of us knows that yet. My mother will tell me over the phone, “Remember your dentist? Poor thing.” He’ll only be forty, it will happen just under two years from this moment, so right now, as he looks in my mouth, he is gestating a secret pregnancy, a bulbous mass crawling through his intestine, growing, growing, growing. “Looks great,” he says, then leans in, close to my ear–little girls in glittered costumes and bouncing curls dance a jig nearby–he says, loudly, “Just don’t eat corn on the cob.” He moves away, smiling again at me. His wife appears, rests her beautiful head on his shoulder, pebbles of light caught in her jewelry and makeup and glistening hair. I think of my own head, my nearly perfect teeth, wobbling on the stalk of my neck, who built us this way, who would jigsaw us into being, bone and brains as friable, as grindable as coffee beans—“Who’s this?” she says, and when I introduce myself and my dentist explains, she isn’t more friendly. The threaded rope of fiddle and voices uncoils between us, a woman trying to sing Chumbawamba as the microphone moans, then screeches. My boyfriend catches my eye, yells over many bald, shining heads, dozens of eggs, “Outside!” gesturing with two hands, full of beer. I say goodbye to my dentist; he and his wife have turned, transfixed by the woman at the microphone, good times, best times. My boyfriend and I go to the edge of the porch, where a cement wall, just three feet high, a child could fall over, separates us from the river. He hands me the beers and soon cigarette smoke follows him, silver trails corkscrewing around his wrist, his face, we face the river and the trails escape us, they float toward the lavender mountains. I want to be ten again, shrink myself—sitting on the wall, I kick my feet over the green foam kissing the cement, a temper tantrum twisting in my gut, I want to see how he’d love me back then, chubby and crooked and shattered, is it any use trying to know someone after they’ve grown up?

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.