by Kim Kankiewicz

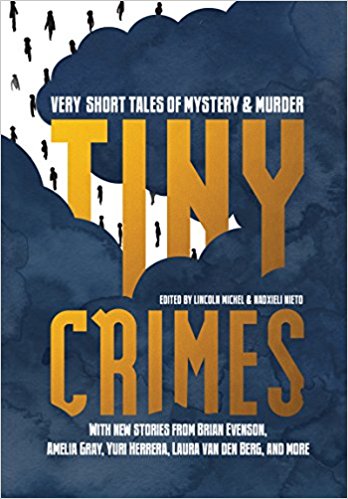

It takes audacity to write flash fiction, to assert that a few hundred words can carry the weight of a story. Memorable flash fiction offsets brevity with boldness, transgressing boundaries and embracing risk. Boldness and risk prevail in Tiny Crimes: Very Short Tales of Mystery & Murder (Black Balloon, June 2018), an anthology of flash fiction edited by Lincoln Michel and Nadxieli Nieto. Bringing together forty established and emerging writers, Tiny Crimes features audacious writing about audacious deeds.

From the first story, J. Robert Lennon’s ‘Circuit City,’ we are privy to the brazen acts of ordinary people. Lennon’s characters plan a movie-style heist at the big box store where they’re employed. The crimes become increasingly flagrant as the anthology progresses. A woman makes empanadas from the remains of IRS agents in Richie Narvaez’s “Withhold the Dawn.” In Lauren van den Berg’s “Friends,” a woman’s moving preparations include abducting a friend to accompany her. In “Minor Witchcraft” by Chiara Barzini, two women enact fiery revenge on a bride who tormented them as adolescents. Barzini’s narrator articulates a reckless impulse that motivates characters throughout the collection: “I sat in the middle of the room like a real witch, focusing on what spell might cause the biggest uproar.”

If the delinquencies in Tiny Crimes are daring, the writing is more so. Carmen Maria Machado tells a heart-stopping story in a single, multi-page sentence in “Mary When You Follow Her,” evoking the nonstop brutality toward women of color. Adam Sternbergh’s mind-bending “Loophole” is a segmented story that takes place in a simultaneous past and present. In “Good Hair,” Marta Balcewicz blurs the line between author and character.

Collectively, and paradoxically, it’s what the narratives omit that makes this anthology so satisfying. Writing flash fiction is always a question of what to leave out. In Tiny Crimes, the writers turn this challenge into an advantage. Several stories use omission to intriguing effect: Christian Hayden’s “Exit Interview” is a one-sided phone conversations. Sasha Fletcher’s “nobody checks their voicemails anymore not even detectives” is a series of voicemail messages left by one woman in her employer’s mailbox. Adam Hirsch’s “Airport Paperback” takes the form of a letter with redacted text. These stories leave readers to construct a context by imagining the person on the other end of the communication and by filling in the missing dialogue and text.

For flash readers, discovering what’s hidden between the lines is motive to read the next. Information gaps engage our minds and tingle our spines. So too with crime fiction, where suspense is paramount. Tiny Crimes proves that just as crime is an apt subject for flash stories, the necessity of omission makes flash an ideal form for crime fiction. In story after story, Tiny Crimes keeps readers in suspense by withholding the who, what, where, or why. “The Trashman Cometh” by J.W. McCormack and “See Agent,” by an anonymous writer, are eerie riffs on the traditional whodunit in which the perpetrators’ very essence remains a mystery. Ryan Bloom’s “The Hall at the End of the Hall” and Henry Hoke’s “Actual Urchin” withhold details of the crime itself, guiding readers to flesh out what happened. Setting is ambiguous in Adam McCulloch’s “Meme Farm” and Fuminori Nakamura’s “No Exit,” leaving us to wonder where the characters are and how they got there. “Any Other” by Jac Jemc and “We Are Suicide” by Benjamin Percy raise questions of motive, while the premise of Michael Harris Cohen’s haunting “A Bead to String” is that we can never know why people do what they do. “That’s how it is,” Cohen’s narrator asserts. “And there’s not a question or an answer or a why that will ever span the distance.”

Indeed, mystery readers who like questions answered and offenders brought to justice won’t find such tidiness here. Tiny Crimes is more concerned with interrogating than upholding our notions of justice. Adrian Van Young’s “The Rhetorician” exposes the oppression of punitive justice, and Julia Elliott’s “Knife Fight” considers the nature of justice in a world where immortality is possible. In “Nobody’s Gonna Sleep Here, Honey” by Danielle Evans and “What We Know” by Misha Rai, desperate characters respond to larger systems of injustice. Charles Yu’s “Alibi” makes us all complicit in injustice. Among such narratives that resist easy answers, Wesley Allsbrook’s illustrations are perfectly at home. As a series, these drawings probe our expectations of women in crime fiction and revise archetypes like the femme fatale and the female victim.

Like a perfect crime, every detail of the anthology is meticulously conceived and executed. The book is compact in size, with cover flaps to mark your page. Inky fingerprints illustrate the margins, in the spot where you’re likely to hold the book. Even the book’s index deserves a close look, offering entries like “Cat – with weird eye infection” and “Turnstile – hopped by nun.” From cover to cover, Tiny Crimes is appealing in design and compelling in content. It’s an anthology to read and reread, for pleasure and to inform our own audacious writing.

Kim Kankiewicz has written for Creative Nonfiction, Colorado Review, NPR, O, The Oprah Magazine, Full Grown People, and other publications. She is pursuing an MFA in fiction at the University of Kansas. Find her online at kimkankiewicz.com or tweeting sporadically as @kimprobable.

Kim Kankiewicz has written for Creative Nonfiction, Colorado Review, NPR, O, The Oprah Magazine, Full Grown People, and other publications. She is pursuing an MFA in fiction at the University of Kansas. Find her online at kimkankiewicz.com or tweeting sporadically as @kimprobable.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.