by Ashley McGreary

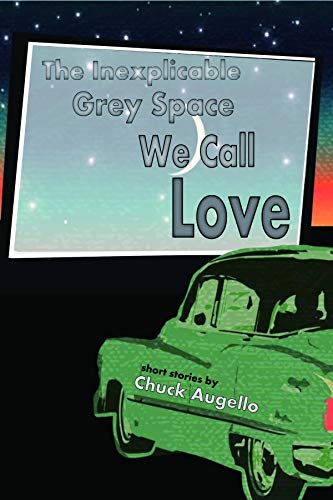

We are fascinated by liminality, that infinite, ambivalent plain existent between possibilities which we call a greyness, an ambiguity, a resistance to arbitary definition, and we read to inhabit that place. Chuck Augello’s debut collection: The Inexplicable Grey Space We Call Love (Duck Lake Books, 2020), crafts this fascination into fourteen short stories, which explore the neuroses of love and loneliness by dealing harsh human experiences a surreal, sometimes absurdly humorous, hand. Elements of black comedy combine with poetical awareness, an overarching search and desperate grasp for meaning, undercurrents of uncertainty and fear, and small flare-lights of redemption in the collision of connection and variegated forms of loving someone. This collection was never written with our current times in view, but its applicability to the experience of us all, in our own harrowing liminalities, cannot be understated. It is a provision of hope, a fascinating and elusive distraction, a chance to laugh and feel close to people again, when that simple intimacy is at a premium, and maybe it throws just enough human light to dilute these dark, tragic days.

Augello’s work first appeared on Smokelong Quarterly back in December 2012 with the brief but powerful soundbite: “Call Me Your Unbroken,” a punch of untapped possibility with the tempo of an alternative rock song. A failed musician reconnects with a past creative partner in the aftermath of a wedding and plays the chords of a transient future: “It was like all the drive and passion we had once put into the band had crystallized into a single moment in that hotel room,” a moment that gives birth to a literal metaphor. In the space of thought, her belly bows outwards, “round and wide” with anticipation, and a creative endeavour is solidified with a shrill cry, “our baby’s cry, and there it was: the best song we’d ever written.” Their reconnection becomes something fragile, defenceless, symphonic for a brief, out-of-time suspension, and then it is over, defiled by an exterior world: ‘she held our baby over the balcony ledge. Then she let go,” leaving each of them wondering about the reality of experience. This story is characteristic of Augello’s collection in that it offers no easy solutions, it is not in the business of answers or closure; The Inexplicable Grey Space We Call Love does not attempt to explain, only represent the varied responses to loving or losing someone. It sits with ordinary lives, filled with extraordinary stories, and writes the simple complexity of living.

It is about the abstract actions of grief, whether this is the space between power and powerlessness, as in “The Prerogatives of Magic,” where a child utilizes imagination and self-possession to shield herself from family breakdown: “Mommy’s gone,” Chloe says, “I made her disappear,” turning what she cannot control into a decisive action. Or the commonality of trauma in humans and animals, represented in “All God’s Children,” which explores the deepest perversions of love, when “an unemployed Army vet missing half his left foot and wondering how toy avoid the rest of his life,” and a rescued capuchin monkey, with “his serial number tattooed on his gums, his lab ID a permanent mark,” run the gauntlet of police to remain together in the absence of the person who united them. The raw, brutal honesty of this collection is something that can only be expressed with an ironic slant; unsurprisingly, therefore, it is also wickedly funny, with pieces like “Thursday Night At The Tick Tock Diner” parodying our self-serving, interior lives, and the space between thought and action, when various people attempt to help “Mr Anderson, the insomniac” as he starts choking on “a halfchewed chunk of blueberry pie,” but are prevented from heroics by their own endless mental digressions. “Extraction” ties these tragic, comedic themes together in the single best opening line: “I was already late for a dental appointment when she told me my father liked to wear lingerie,” which revels in the absurd necessities of coming to terms with loss, and accepting the fact of missing someone.

Augello focuses in on the moments that are often shut out of stories, he gives isolation the freedom to be connecting, and the piece that provides name to this collection, “Cool City,” is no exception. In a “lonely and aggressive” metropolis, love is stripped of all sentimentality and becomes a conveyer-belt search for an arbitary match on the precept that “if you really take the time to get to know someone, you’ll find thousands of reasons not to love them.” This indifferent city becomes a backdrop for exploring fixation, ritual, dependence, resistance to change, and the importance of asserting meaning onto the everyday: things that cannot admit love. Then, inside the destructive epicentre of a hurricane, with all patterns suspended, connection becomes a simple, meaningful, throwaway act, which represents something greater than itself: “She handed me a small camping grill and a canister of propane, […] in that moment, I think I understood the inexplicable grey space we call love.” Obsession and fixation, verging on the metaphysics of addiction also play out in “The Project” which depicts a truly harrowing subsuming of the individual to their work, and the individual to the individual: ‘Tattooed over her body was the code from Phase Four of the project […] Large blocks of html covered her abdomen,” where love literally becomes skin deep and completely impersonal. This collection strings out connections like spider’s silk, but not all of them have the capacity to be redemptive, some are just there to hold people steady in an infinite space, and, sometimes, their entrusted never cut them loose.

Augello plays on every emotion, and draws out the stories they have to tell, whether that is a pizza cook catering a self-immolation, or a man, ruled by past mistakes, agreeing to burn down his brother’s house for insurance fraud because he doesn’t have the privilege of moral absolutes. There are parallels and compromises in this sumptuous collection, repeated motifs that are both dreamlike and destabilising. It is unique in conception, expansive in scope, and, in the words of Rainer Maria Rilke himself, guides “Your vast shell [to reach] into endless space.”

________________________

Ashley McGreary is a fledgling writer with a degree in English and Creative Writing, currently working towards an MA in English Literature. She is at the extreme end of starting out, but hopes eventually to shape a career out of the two things that set her soul on fire: literature and writing.

Ashley McGreary is a fledgling writer with a degree in English and Creative Writing, currently working towards an MA in English Literature. She is at the extreme end of starting out, but hopes eventually to shape a career out of the two things that set her soul on fire: literature and writing.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.