Reviewed by Lisa Slage Robinson

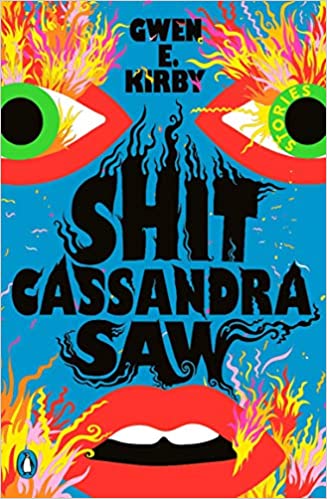

Subversive, irreverent, and unrepentant. The twenty-one flash fictions and short stories in Gwen E. Kirby’s debut collection, Shit Cassandra Saw are laugh-out-loud funny and deeply illuminating. Kirby’s kick-ass female characters speak the truth, foretell the future, demand to be heard. They cuss. They refuse to apologize. They are Japanese warriors and cross-dressing pirates, Celtic queens reincarnated as baseball players, single moms, and Midwestern girls. They are not marginalized. They are not victims. They arrive on the page with sass and agency. In conversation with myth and history and contemporary popular culture, Kirby offers a marvelous stew of women throughout the ages, no longer Cassandras condemned because they refused the advances of men and gods, their collective wisdom no longer dismissed as the hysterical ravings of lunatics.

In the cheeky monologue “Shit Cassandra Saw That She Didn’t Tell The Trojans Because At That Point Fuck Them Anyway,” which first appeared in SmokeLong Quarterly, Cassandra is done telling men what she knows. She is “done, full the fuck up, soul weary.” Instead, she will tell the women of Troy because “they know that Cassandra’s curse is their curse as well.” For women she will reveal a future with tampons, and jeans and washing machines, the cordless Hitachi Magic Wand, elastic hair ties and epidurals. Then she muses about what Trojans will become – something to “be carried in every hopeful wallet” and how women will rejoice as they are unfurled.

With this collection, Kirby answers the call of the French feminist and literary theorist Hélène Cixous who urged women, in “The Laugh of Medusa,” to write their bodies, to write themselves into history, to revise the patriarchal narratives which perpetuate the repression of women “in a manner that’s frightening since it’s often hidden or adorned with the mystifying charms of fiction.”

And so, Kirby summons the voices of historical figures from bloody battlefields and pirate ships.

In “Nakano Takeko is Fatally Shot, Japan 1868,” the fatally wounded Nakano Takeko asks her sister to behead her so her body will not be taken by the enemy as a trophy.

In “Mary Read is a Crossdressing Pirate, The Raging Seas, 1720,” Mary Read joins the British army as a man and is later pressed into service on a pirate ship, taking both male and female lovers. After the ship is captured, Mary notes that it is easier to be a man in both life and death. The men are hanged and die swiftly. Mary is spared because of the pirate child she grows in her belly only to suffer death in the long, brutal and bloody battle of childbirth.

In “Scene in a Public Park at Dawn, 1892,” Kirby reimagines a duel between two Victorian ladies as recounted by the attending female physician. To avoid infection should dirty fabric be pressed into their wounds by the tip of a rapier, the physician orders them to remove their upper garments, their shirtwaists and corsets and chemises. And so, they duel topless, their breasts freed, unbound.

They breathe deep for the pleasure of it. They shake hands. They strut. They speak. It’s all bravado, a script we have read in novels and watched on stage. Is this how men speak? How dare you. You presume too much. I’ll repay your insolence with blood. They are dueling over a flower arrangement, who copied whom, and it would be easy to think them ridiculous. But I don’t. As if men duel over anything better, shooting each other over the imaginary flowers we press between our legs.

The contemporary women in these stories are not exempt from the challenges of finding and claiming their voices and in many ways must fight their own complacency – a false sense that things have already been resolved. Because what it means to be a woman is constantly being re-litigated. Is it clothes and a womb that makes her a woman? Is she entitled to power or must she use her education and wits to conform to outdated notions of gender roles and body autonomy, and impose them upon others like a modern day Phyllis Schlafly or Amy Coney Barrett, the latest addition to the U. S. Supreme Court. And what to do with that power once she has accessed it – use it like a man or use it like a woman? And if she uses her power, is that an attack on masculinity? Or is it just an act of emancipation?

In “Here Preached Last Night,” the narrator, a teacher and soccer coach, is haunted by the 18th-century evangelist George Whitfield. She revels in the preacher’s accusation that she is a whore because she is having sex with fellow teacher Karl. Karl winces when she calls it what it is: “fucking.” Karl doesn’t like her being crass. Karl “doesn’t like to be reminded that [they’re] doing a bad thing for no other reason than it feels good.”

Meanwhile, as the girls’ varsity coach, the narrator is alarmed that the girls hesitate in practice. She pushes the girls to the edge to help them access the depths of their abilities. And when the girls vomit from the rigor of endless wind sprints, she is not tender with concern. She simply notes that they’ll never win by asking permission.

As a counter to what may feel like excessive male bashing, Kirby offers a subtle commentary on #MeToo and cancel culture. In “A Few Normal Things That Happen A Lot,” women fight off predators with super powers which have been conferred by witches, alien mothers, werewolf scratches, bug bites and top secret laboratory experiments. Bother a woman on the street or a subway train, she will bite off your hand or another piece of your anatomy with her newly acquired fangs. Following a woman around in the grocery store making lewd and suggestive comments can be hazardous. If she has been bitten by a radioactive cockroach, she will hiss at high decibels, shatter salsa jars with her voice, spray you with all that broken glass. Violate her space, break into her apartment and she will disappear you with her magical remote control. The tables are turned, men can see women, their fangs, their cockroach antennae, their fingers pressed on the remote. Men carry around cans of Raid like mace. They think twice before they put their hands where they are not welcomed. Women are no longer afraid, there are so many things they can do now. They no longer miss opportunities because of fear. But there are complications: werewolf teeth get infected, the female scientists who tested their experiments on themselves are scarred. “They are proud of what they’ve done. But still, sometimes, they wish they could be smooth and whole, some softer version of themselves.”

There is a sense throughout the collection that while woman can do as man does, given a chance, she might do it differently. And isn’t that the point? Shit Cassandra Saw is poised to become a feminist manifesto – a classic handbook for how to subvert the old narratives, how to write women into history.

__________________________

Lisa Slage Robinson writes to explore invisible landscapes and magical feminism. A finalist for Midwest Review’s Great Midwest Fiction Contest, her work appears in The Adroit Journal, PRISM, Storm Cellar, Lit Pub, Necessary Fiction, Drizzle, Meat for Tea and elsewhere. Previously, Lisa practiced law in the States and Canada.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.