Reviewed by Emily Webber

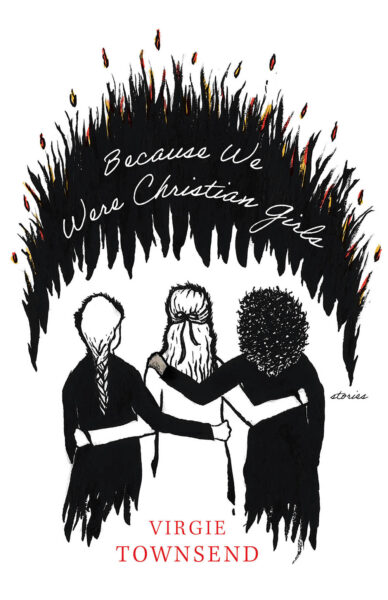

Virgie Townsend’s chapbook of seven stories, Because We Were Christian Girls, illuminates the experiences of girls living under the pressures of Christian fundamentalism. These stories bring to the surface the interior lives of a diverse group of girls—black girls adopted by white Christian parents, girls raised in the fundamentalist tradition from a young age, and girls exploring their sexuality. Townsend’s strength in this collection is showing girls on the edge of defiance, beginning to understand the constraints and cruelty of the warped logic of the religion pressed upon them, and wanting to find faith on their own terms.

In one of the most moving stories, “What Fundamentalists Do,” a single mother is told by their pastor that her daughter, Sarah, asks too many questions, so she brings her to a more charismatic church to be prayed over. Sarah doesn’t want to be there, but it ends up being an unexpected moment of understanding of her mother’s motives and faith and her own. Sarah gives in to the laying on of hands by the pastor but prays her own way in her heart. “When I pray I feel the love of God running through me like a steel beam, and I know in my proud, defiant heart that my faith is real.” It is a turning point in the story, a moment where a transformation begins and Sarah wrestles back control from others.

Townsend’s use of a collective point of view, varying lengths, and even some fantastical elements like a whale in the belly of a girl and a burning bush that erupts in a girl’s bedroom lend strength to the chorus of voices and their longing for freedom to make their own choices. As the girls debate over what to do and the significance of the burning bush, we see glimpses of their lives. We see as they learn to use their rebelliousness and that their strength is forming within and rising to the surface. But this religious upbringing will continue to color their world, no easy thing to leave entirely behind: “For the rest of their lives, Shayla, Meg, Abby will argue about it: what the burning bush means and who holds the power to say what it means and how they’ll live with it.”

Another surprising aspect of these stories is that while they are centered on the girls, in bits and pieces throughout we see the lure of fundamentalism for the adults. In the first story “Running,” the girls observe their parents: “We don’t know it yet, but the past is always at their heels. Its teeth are sharp, its mouth void.” Throughout the collection we see bits and pieces of the adults’ lives—they are looking for stability, for immortality, for community, for control over a messy life, or atoning for mistakes they made in the past.

Townsend only falters in “Heavenly Bodies”, where a family Christmas dinner between believers and non-believers goes predictably awry. The exchanges between the characters come off as oversimplified and awkward. Yet at the end of that same story Townsend wrangles it back to deliver a quiet, but explosive ending as one girl images being left behind in the rapture.

There’s a balance in the collection, no loud anger against religion but a quieter, interior defiance against forms of religion that seek to control and what that strips away from a person. These girls are not rejecting the idea of faith, they just want to find their own. Because We Were Christian Girls shows true moments of grace and celebrates the small victories of girls finding their way out from under the shadow of Christian fundamentalism.

Because We Were Christian Girls is available from Black Lawrence Press.

__________________________

Emily Webber’s writing has appeared in The Writer magazine, the Ploughshares Blog, Five Points, Maudlin House, and Brevity. She’s the author of a chapbook of flash fiction, Macerated, from Paper Nautilus Press. Find more at emilyannwebber.com and on Twitter @emilyannwebber.

Emily Webber’s writing has appeared in The Writer magazine, the Ploughshares Blog, Five Points, Maudlin House, and Brevity. She’s the author of a chapbook of flash fiction, Macerated, from Paper Nautilus Press. Find more at emilyannwebber.com and on Twitter @emilyannwebber.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.