by Amanda Krupman

I began eating candied ginger this spring so I could feel something. In the first week, I ate it by the handful: My tongue was titillated and grateful. There were potato chips soaked in vinegar in week two, and every morning for six weeks, crunchy peanut butter on toasted seedy bread. I longed for nuance, for flavor, but that is lost with anosmia; in a panic, I grasped for outsized sensations, for anything with bite.

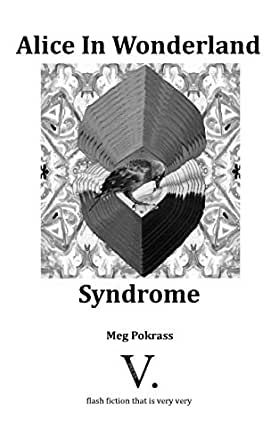

With symptoms unresolved by summer, and an added distortion (the phantom smell of sour milk), I was primed for the conceit of Meg Pokrass’ Alice In Wonderland Syndrome (V. Press), a flash fiction pamphlet named after an actual neurological condition (which refers, of course, to the classic story).

Those suffering from AIWS cannot trust many of their senses—perceiving their bodies and objects in the world as larger or smaller than they actually are, and losing their sense of time. Accordingly, in the opening flash, “Upside-down Rooms,” the protagonist “shrinks in the middle of the day,” her fingers large and “heavy as a truck,” and is sure the “dogs are bigger than both” she and her husband, who “doesn’t believe in crazy-ass syndromes.” In the following story, “Rabbit Boy,” time is circular: “She catches up with the scent of him again between her house and the house next door, but it is forty years later. She is still the girl and there is his scent.” And in “Maladaptation,” a woman visits a number of therapists, and while they are “are all about leading the way…[s]ome of them, most of them, seem as confused as she is. She is not sure who should be paying whom. Nobody is doing very well.”

A skewed sense of time and space, confused clinicians: any reader that has had to shelter-in-place for months might find that these stories resonate. But even outside of the strangeness of life during a pandemic, many of us will recognize the syndrome as Pokrass likely intended: an emotional metaphor for the malleability of brain and body in times of discombobulation and grief.

Committing to this metaphor of altered perception, Pokrass can be both substantively and mechanically playful. In “Tryst,” a one-sentence story progresses between multiple settings, conversations, and an untethered point of view—the omniscient narrator beamed between clauses at the speed of light. In “Wealthy Suitor,” the suitor “happy as a schoolboy…tucks her into the pocket of his $13 Walmart jeans.” The story continues:

She plays with his hard, linty strings. Makes plastic noodles from his thread.

There is something almost satisfying about the safety of his pocket. She sings inside his pocket and she sings about his pocket.

“This does nothing for my bad hip alignment,” he whispers.

A year goes by and she doesn’t want to come out. Sews the opening shut.

These 29 micro stories, which can be read in one sitting, are so interconnected that the effect is of one short story, told in fragments—a fitting format for a meditation on the unraveling of a marriage, with guest stars (dogs, lovers, therapists, the tiger cat, a rat). The compressed power of flash, however, combined with Pokrass’ lyricism, invites the reader to re-read each piece, and unpack each morsel line by line. Consider “Hope,” which reads like a prose poem:

There are lies in tiled kitchens gleaming with light. And in warm restaurants, where the Merlot is recommended by the waiter.

There are lies in neighbors who, when you become unlucky, roll backwards, away from you, like a sudden, low tide.

Life can be dissected this way.

This has something to do with rules unwillingly broken, trophies not won, disobedient body parts. The signs she ignored when they lay on top like a stiff blanket.

Hope sometimes lives in the music warming the living room at night. And, some mornings, hope pulls at her like a puppy. Asks her just to see the sky and to see the sky.

With gallows humor, I LOL’ed at the beginning of “Bird Promises,” the final piece in the collection: “She lives in a movie called What Happens Next?” At a time when we are all living in said movie, Meg Pokrass’ new flash offering is a reminder that, while this collective unmooring is new and unsettling, our emotional lives have already pulled us through a great many rabbit holes. At times surreal, at times elliptical, Alice In Wonderland Syndrome is ultimately an earthy and poignant grouping of flash fiction for an upside-down world.

_____________________________

Amanda Krupman’s work has appeared in publications including Flapperhouse, The Forge Literary Magazine, BLOOM, The New Engagement, and Punk Planet. Amanda received an MFA in Fiction from The New School’s graduate writing program and was recently a recipient of a Jerome Foundation Emerging Artist Residency Award. She teaches writing at Pace University and “From Page to Podcast: Writing Audio Fiction” at Middlebury College. She is currently working on a collection of short fiction. Follow her on Twitter: @akrupman

Amanda Krupman’s work has appeared in publications including Flapperhouse, The Forge Literary Magazine, BLOOM, The New Engagement, and Punk Planet. Amanda received an MFA in Fiction from The New School’s graduate writing program and was recently a recipient of a Jerome Foundation Emerging Artist Residency Award. She teaches writing at Pace University and “From Page to Podcast: Writing Audio Fiction” at Middlebury College. She is currently working on a collection of short fiction. Follow her on Twitter: @akrupman

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.