by Grant Faulkner

One of the most frequent questions I’m asked about writing one-hundred-word stories is whether a one-hundred-word piece can have a plot since it has so few words. The answer is that, yes, miniatures can have a conventional plot with a beginning, middle, and end that includes character change—but they also open themselves up to a different kind of plotting that I find more interesting.

One dominant plot model that has come to be accepted as gospel comes from Joseph Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces, in which Campbell posits that there is a common mythological structure of storytelling, which he calls “the hero’s adventure”: “A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

Campbell’s theory, which is similar to the popular Freytag’s Pyramid, has permeated writing workshops and authors’ psyches, yet we should ask if this plot structure actually reflects life in the way we experience it. Do we live lives that mirror an adventure quest? If we live lives that “rupture,” “splinter,” “suspend,” “interrupt,” “dissolve,” “mix,” “scatter,” “swirl,” and “compress,” how can we be expected to render them in a form that speaks to wholeness and cohesion? In fact, instead of reading for the escalating action embedded in Campbell’s structure, what if we read a piece just for its tone, its lyricism, its mood, its intensities? Can such elements supersede plot?

Plot is a statement about reality, a commentary on how life is lived. I wonder how the supposedly “plotless” story is full of a different kind of plot, one that is more nuanced and subtle. “The shorter the piece of fiction, the less need for a plot,” said Jerome Stern. “You can write a fine story in which little happens: A man curses his neighbor, a widow quits her mahjongg group, or an unhappy family goes on a picnic. Simple shapes work better than something fussy and complicated.”

Perhaps such a story isn’t without plot so much as it is full of a kind of plot that requires a deeper kind of noticing from the reader. Some short-shorts certainly have a less discernable beginning, middle, and end. They eddy, as if they’re leaves floating along the slow meandering of a creek. A tiny tale can be like a loop, looping through other loops, creating a quilt, a mosaic. They tend not to propel you forward, as in seeking what’s next, but to hold the world in place for one dramatic moment.

I’ve heard people say that flash has no room or time to linger, that it’s all about that bright moment of illumination, a dramatic act, but I question that. Perhaps a short-short can linger the way we linger on a street corner, not realizing the light has changed. Perhaps a story can be as much about a mood as it is about an action. The moment can matter as much as a series of moments. A lyric impression, a series of lyric impressions can move with escalating tensions. Why not? Could it be enough for a work to simply be expectant with meaning?

This isn’t to say that short-shorts don’t need momentum. Every work, whether it’s a six-word story or an experimental novel or even an anti-novel, needs momentum of some sort. But it’s up to the author to decide what the elements of momentum are. Does momentum arise from direct action (a character desires something, encounters an obstacle, acts), or does it arise from the “subtle, progressive buildup of thematic resonances,” as David Shields puts it. One can create momentum through an image, a mood, a voice. It’s harder to pull off, but the reward is often more satisfying and more meaningful.

“A short story, in its brevity, may not have a fully developed plot, but it must have the essence of a plot, yearning,” said Robert Olen Butler. Yes, yearning. Not a series of plot points that map to a structure, but a yearning, a restlessness, that takes a story from one moment to another with uncertainty lacing itself through the prose.

To yearn in a state of uncertainty means writing toward the mystery, toward the questions. Even though we seek answers, we also know that the answer often isn’t the answer. Or that sometimes an answer is insufficient. If a writer is pursuing a mystery, that’s a type of plot unto itself. We can feel that anticipation, the suspense that naturally resides between the known and the unknown, the opening up of questions.

“If mystery, the genre, is about finding the answers, then mystery, that elusive yet essential element of fiction, is about finding the questions,” said Maud Casey.

All stories must possess mystery. They either offer a frame in which the reader tries to solve the mystery, to know what happened, or they are mystery itself, each sentence, each scene, built around questions that go unanswered.

Brevity is built with questions, forms itself around questions, nurtures questions, finds its breath in questions. It’s not a style that seeks to speak with certainty, but with nuance.

Brevity naturally provides an opening to mystery because the mysterious eludes all words of explanation. It speaks to something more significant than what can be explained. There is always something beyond.

“Mystery in fiction means taking the reader to that land of Un— uncertainty, unfathomability, unknowing. It’s Kafka’s axe to the frozen seas of our soul. In other words, it will—and it should—mess you up,” said Casey.

A plot-driven narrative seeks resolution and conclusion whereas works of brevity often seek irresolution. These are stories that hang in the air, unfinished. Jane Alison describes such a narrative as a narrative of wavelets: “Dispersed patterning, a sense of ripples or oscillation, little ups and downs, might be more true to human experience than a single crashing wave: I’m more likely to feel some tension, a small discovery, a tiny change, a relapse.”

Instead of dramatic action, can’t the mood of a story—its “dispersed patterning”—be just as important? Can’t such things be their own sort of plot?

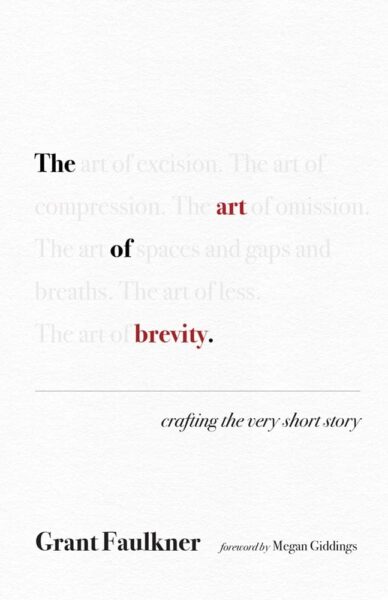

The Art of Brevity: Crafting the Very Short Story (184 pages) is available from University of New Mexico Press.

________________________

Grant Faulkner is the executive director of National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo), the co-founder of the online literary journal 100 Word Story, and the co-host of the podcast Write-minded.

Grant Faulkner is the executive director of National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo), the co-founder of the online literary journal 100 Word Story, and the co-host of the podcast Write-minded.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.