In parts this story recalled for me nothing so much as William Styron’s Darkness Visible, his memoir of depression, in which he describes the “storm of murk” of his experience. Styron’s language is much plainer, though, than your tracing of the “blackened bottom.” Your language is dense and knotty, and I’m wondering to what extent that is being used to mirror the narrator’s state of mind, and to what extent it is being used to resist and oppose the languidness of that state. Or something else entirely?

Certainly storm of murk. Freud referred to it once as the black tide of sludge. Dense language is usually on hand for me as a device, though it varies by whatever the work demands. An Dantomine Eerly, the first book I wrote, had little else to guide the reader except flow of language by itself, which turned out to be extremely obscure, and so for me pretty ineffective. The book I’m in the middle of now has a lot of deep lovely structure to it and, while the primary focus on aesthetic language there maybe more than ever, it may be less insane. Can’t tell yet if that’s good or not. I’m just going to have to make it good. So the language for “We Haven’t Seen You In Ages” is very much dictated by the needs of the flash-fiction form it took. I attempt to convey the most amount of information about a defined but very imprecise event.

In addition to death, there’s a lot about birth and rebirth in this piece. How was this piece born—was it an easy birth, a breach, a C-section. etc.?

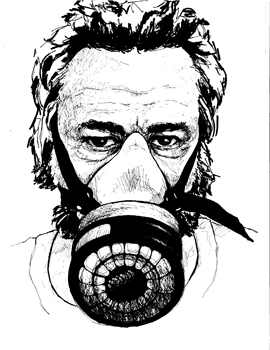

To be honest, the piece is a retrospective of a period of prolonged hallucinogen use that had an intended shamanic and spiritual goal. There is the line, “the odd, lysergic episode (shadowed, photographic suicide),” which is a reference to LSD, specifically one trip where I had an out-of-body vision viewing my own death frame-by-frame, like a film.

That’s why the story is told from the narrative point of view of “waking up” in the forest, coming to and regaining your consciousness of yourself and your bodily orientation as well. That happened literally and figuratively. The trips were a descent from the spatial surface of the world inward, or downward. Where hell was confronted and most definitely passed through. It can be messy and disorienting, which is why thankfully I had preparations, a method, and a guide. Which is how I knew, from a departure, that I had somehow reached my destination. The “blackened bottom” of the soul, the self, world. I reached a goal, which was a strange process in that state. Like being at the bottom of a volcano. It’s hard to know what to do under that much pressure. So you just travel down the one path that seems to be blocked to you, and you push and push and then break through. So yes, birth. Reborn. You flip through, reverse, and come back up the other side of yourself, opposite the way you went in.

I love the relief provided by some of the shorter, simpler sentences in this piece: “Bluegrass banjos softened bonfires at night.” “I tell one I’m glad to be here.” How conscious were you of the rhythms of your sentences in writing this?

As conscious as I can be of that. That’s why they are there. There is a movement in “We Haven’t Seen You” from the complex and immaterial to the simple and the material. So, those lines quoted come near the end of the piece. The entropy of the piece is building up to being back in the world. Going from the chaos of coming apart back to the miracle of performing and completing one simple action in the world. In this case, pulling a lobster trap up from the bottom of the ocean.

The point of view in this story is complicated. Though it is first person, the opening sentence and some of the others feel omniscient or distanced. This effect is furthered by the notion of a split character, one who “acted in the world” as “purely physical pantomime” and some deeper self. And then there is the title, which adopts the first person plural in quoting friends and acquaintances. Can you talk a bit about the challenges that this slippery point of view presented?

Yeah, endemic of both hallucinogenic experience and the variety of states in spiritual transformations—meditation, trance, ego death, schizophrenia, disembodiment, astral projection, enlightenment. You struggle to break from the tyranny of the ego—the first-person rationalizer—then you spend time examining your self as your other—there you have the second person—and then you have complete separation and omniscient interactions, sometimes with a godly voice, a singular powerful entity or spirit that you naturally approach out of its brilliance and gravity, and then being granted access to remote images or removed knowledge—and so you have the third person. I tried to represent the natural flow of one to the other. And suggest that experience is made up of that multiplicity which we are submerged in all the time.

If this story was rooted in myth, it would seem to be that of Orpheus, or some character who similarly returns from an underworld. The final moment, embarking on a boat, feels like an archetypal journey has just begun. What myths—or better—what mythologies, influence this and your current writing projects?

Interesting. With “We Haven’t Seen You” I didn’t choose a myth as a muse. It depended more on the ingredients of spiritual change as myth themselves, which they are. They have been typified in sage figures, the hermitage of monks and those who choose paths of enlightenment, becoming gods/goddesses. But I told it in first person because it was an “account of wreckage and its aftermath,” my account, one of many, and I didn’t want to tell a hero or sage myth. Which I probably will in longer form in the future.

What myths are influential? The novel I’m writing now, called Darkansas, is about two twin brothers who return to their father’s home in the Ozarks on the Arkansas-Missouri border for one brother’s wedding. While they are home, the brother who is not getting married discovers a secret in their family history that every generation of males going back to the end of the Civil War have been twins and that each generation one of them ends up murdering their father. So, I build that plot using a Navajo legend called Slayer of Alien Gods and Born From Water, who were two brothers born to the first earth woman to kill alien gods to make earth safe for human civilization. Then I mashed it together (a la Campbell’s Creative Mythology) with a Greek myth called the Arician Grove, where the cult of Diana performs a fertility rite on the Spring equinox. In the grove, anyone can challenge the king to a fight, and if you succeed in killing the king, you become the king.

Without going into these two wonderful myths too much, one of the great things they have in common is a strange moral dimension involving absolution—or exemption entirely—from the “sin” of murder. In the Navajo myth, the brothers cannot be aware of the tasks they were created to do. So murder takes on a being or a natural function that leaves no room for moral reflection attached to it. And in the Grecian myth, you become the king by killing the king, thereby condemning yourself to your own death, because the next king will inevitably have to kill you. That’s a fascinating moral dimension. Killing the king is not absolutely wrong because, at its end, it is a killer being killed. Which is one of the tenets of our society’s often odious mechanisms of justice. Put that in the Ozarks with some minor Civil War history, karst hydrology, guns, and the history of bluegrass, and it is a story that is so fun to write. Which is the point. Life is too painful not to have fun on the page, which is where I spend the majority of my time, anyways.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.