Art Taylor is giving away a copy of his new book, On the Road with Del & Louise: A Novel in Stories to the author of the story he selects for publication.

What was your writing process like for On the Road with Del & Louise?

On the Road with Del & Louise is subtitled A Novel in Stories, but when I first began writing about the title characters, it was just a single story—with no plans to carry them beyond that tale. It was a few years after the original story, “Rearview Mirror,” was published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine that I began to wonder what happened next to Del and Louise: small-time criminals trying to build an honest life for themselves but failing every step of the way. Following this unpredictable pair was as much an adventure for me as I hope it will be for readers, and I enjoyed the process of writing individual stories (a real estate scam, a wine heist, a Vegas wedding chapel hold-up, etc.) and then building them together to tell the longer story of a couple trying to figure out themselves, what they mean to one another, where they’re going in a bigger sense.

How did you get started writing mysteries? In academia at least, the writing and construction of a strong mystery short story or novel doesn’t seem to be regularly taught.

I’ve been a fan of mystery fiction since I was a young child. Encyclopedia Brown and Nancy Drew were among my favorites—and really among my first friends in many ways. But when I began writing myself, I didn’t immediately start out in the genre I most liked to read. Maybe it has something to do with preconceptions about the type of storytelling I should be concentrating on, but my earliest fiction in high school was more clearly influenced by Hemingway than by Hammett, and it took several years (many) before I came back to embrace the genre more fully.

Whether that slowness or reluctance was the result of some prejudice against genre fiction on my own part, I do think that those kinds of judgments persist in many writing workshops and academic programs. Having gone through an MFA myself, I don’t recall any of my graduate-level peers writing genre fiction, and when I see genre fiction in the undergraduate workshops I teach, it’s more likely to be fantasy fiction, not crime fiction. (And I know of at least two graduate-level professors who, when they taught undergrad workshops, forbade students from submitting fantasy or science fiction at all.) To my mind, teaching students to write well in their preferred genre should really be the goal—rather than inflicting storytelling preferences on aspiring writers—but even for those students who are aspiring toward literary fiction, I think that exposure to genre fiction can help to develop skills at building solid plots and not just at writing stellar prose. (The two are not, of course, mutually exclusive.) I’m actually teaching a graduate-level course at Mason this semester that looks at crossing genres—at what beginning writers might learn from reading and their trying their own hand at crime writing.

What are some literary fiction stories (that could be used to teach someone about writing an interesting mystery?

Most folks equate mystery fiction with detective fiction—whether that’s an amateur sleuth or a hard-boiled gumshoe—but I think that’s ultimately limiting. I prefer the term crime fiction ultimately (one more common in the UK, as I understand), and even there I think that definitions and boundaries blur—and have blurred for a long time in terms of genre.  Both Cleanth Brooks and Peter Brooks—leading literary critics—have likened Faulkner’s Absalom, Abaslom! to the detective novel.

Both Cleanth Brooks and Peter Brooks—leading literary critics—have likened Faulkner’s Absalom, Abaslom! to the detective novel.

The Best American Mystery Stories of the Century, a pretty widely available anthology, includes John Steinbeck’s “The Murder,” Pearl S. Buck’s “Ransom,” and Flannery O’Connor’s “The Comforts of Home” among its contents (and the mention of O’Connor reminds me of O’Connor’s “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” and of Eudora Welty’s terrific “A Curtain of Green,” both of them brimming with violence). Stories by Alice Munro—who could be more literary?—have regularly been included in the annual Best American Mystery Stories series; I’d suggest “Child’s Play” or “Free Radicals.” And in my own classes, I regularly teach Jorge Luis Borges’ “Death and the Compass,” a story influenced by and steeped in the traditions of Edgar Allan Poe’s seminal detective C. Auguste Dupin.

When do you know a short story is ready to be sent out?

I’m often a very slow writer—at all stages of the process: getting the first draft done, diving in for revisions, diving in for more revisions. No matter where I’m at, I nearly always feel like there’s more work to be done. Even after I submit a story, I sometimes still find myself tinkering with it. After a recent acceptance by Crime Syndicate Magazine, I wrote the editor and told him I’d kept working on it after I sent it and could I send him the new files? I submitted another story just before Christmas, and almost immediately I was tweaking, adding, subtracting. We’ll see what happens if that one gets picked up.

Related maybe: I try to never read my work once it’s been published, because all I see are the places that still need work.

Let’s say a wealthy family that loved writing approached you to ask how they should spend their money to develop and encourage writers. How would you tell them to spend their money?

Two things leap to mind here. The first would be the development of a writers colony or writers retreat; the biggest issue that faces many of us writers is finding time to develop our craft or to pursue ongoing projects. The second would be some project-in-schools program at early stages of education: elementary school, middle school, in there—and maybe particularly in underserved communities. There’s a ton of talent out there, and we just need to find ways to encourage it, from our earliest writers through emerging artists and even to established writers who are too often still struggling to fit their creative work around busy day jobs. Many ways to serve the arts.

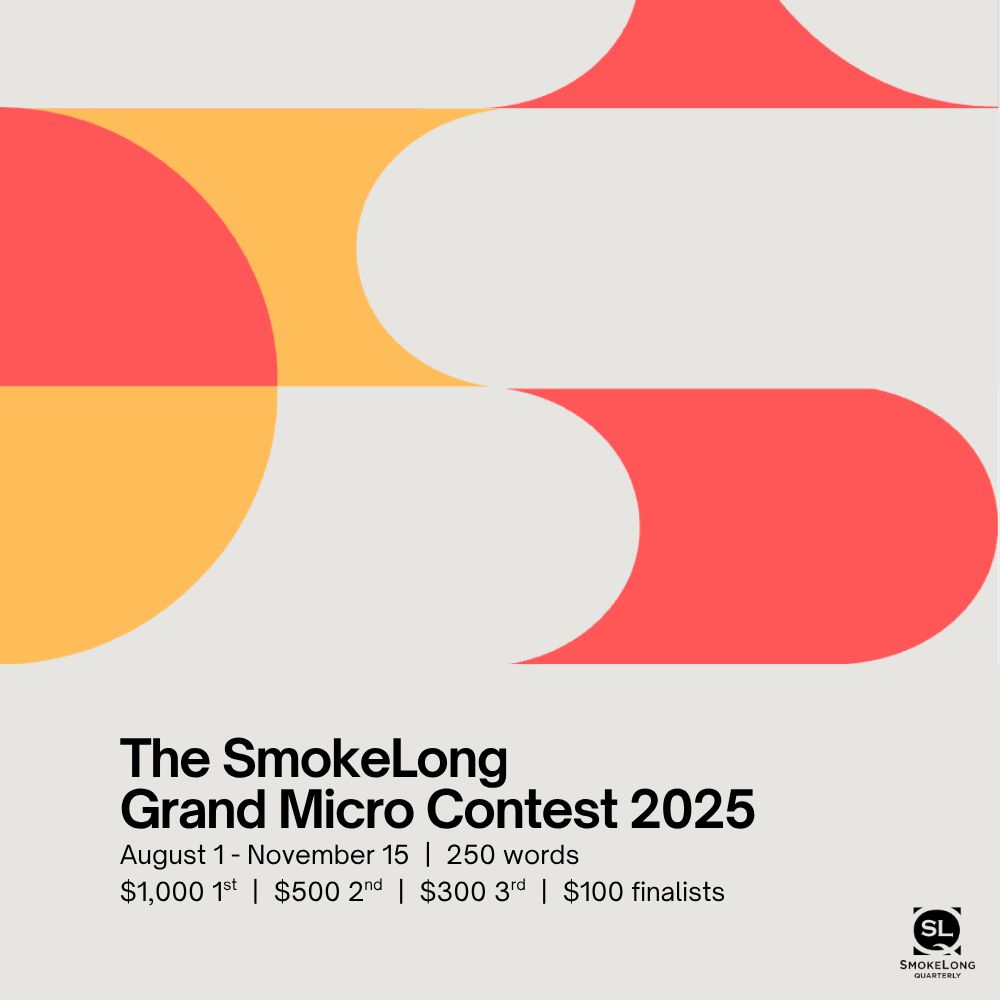

The SmokeLong Grand Micro Contest (The Mikey) is now an annual competition celebrating and compensating the best micro fiction and nonfiction online.

The SmokeLong Grand Micro Contest (The Mikey) is now an annual competition celebrating and compensating the best micro fiction and nonfiction online.