Interviewed by Maitlyn Harrison

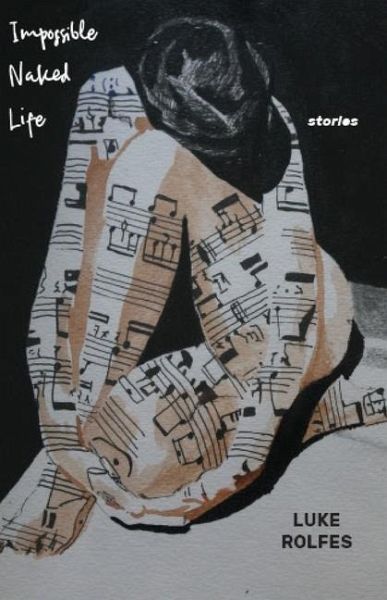

Maitlyn Harrison: Congratulations on Impossible Naked Life being named the winner of the Acacia Fiction Prize. I’m always interested in the way manuscripts develop. Could you talk a little bit about how the stories in this book became a collection?

Luke Rolfes: In the earliest stage of this book, I built a collection of flash fictions that were all called fables. The first one I wrote was called “Fable #1: Des Moines, Iowa,” and then “Fable #2: Sunlight Peak, Colorado,” and so on and so forth. I liked the idea of having a cohesive and tightly stitched, place-driven manuscript, but all the flash fictions were behaving quite differently and moving in various directions. Some didn’t feel much like fables at all. After some time, I scrapped the numbered titles and stopped referring to them as fables. I found that I liked them better if they had individual titles.

At the time of building Impossible Naked Life, I was reading collections and anthologies of flash fiction. I had thirty to forty really short pieces that I thought went together, and I started to craft a few longer pieces that could break up the pacing. These longer pieces became anchors to which the flash fiction could float around, and I liked the structure that emerged.

MH: In the flash fictions, images play a really important role in the stories’ success. How much do you think you’re drawing on the conventions of poetry to inform them? Do you also think of yourself as a poet?

LR: I’ve never thought of myself as a poet, though many of my friends are. I blame/credit all my poetic instincts to the poets in my circle. My co-editor at Laurel Review, John Gallaher, has a wonderfully unique and prose-adjacent style to his poetry, and we often send each other pieces in progress or bounce ideas back and forth. I think that when writers put their heads together often enough, they begin to borrow from each other stylistically.

My favorite part about poetry is the ability of poems to leap between seemingly unrelated images. I wish I could do that in long-form prose, but I feel compelled to connect the dots.

Flash fiction, for me, isn’t bound by the same narrative rules as longer fiction. It is often experimental and rarely follows a traditional story arc. In my work, especially flash, I have two to four images I want to show the reader. The story itself is sometimes me just manipulating the reader’s eyes to go to those two to four images.

MH: The Midwest is full of cliches—miles of farmland, more churches than Starbucks, a place to flyover, but never actually visit. However, in these stories, the Midwest is transformed into something surprising and new. What were you hoping to do with this setting?

LR: The Midwest is an interesting place. In some ways, it’s incredibly singular and unique. In other ways, it’s mundane. There’s a whole lot of space but a relatively small cast.

There’s a special connection Midwesterners have with the landscape. Driving through a gravel road, surrounded by crops—that feels important, somehow. You can sense it, maybe.

In turn, Midwestern small towns are ubiquitous and idiosyncratic at the same time. They are all more or less the same—a Casey’s gas station, a town square, a large pine tree by the courthouse that lights up during the holidays—but some of them have incendiary histories. For instance, there’s a town near Maryville, where I teach, called Skidmore—which is home to several of the most disturbing murders one could imagine.

There’s something, too, about the lack of oversight in “flyover country.” So much space. So few people. The isolated communities sometimes behave like standalone kingdoms rather than parts of a larger state. I’m fascinated by those tendencies, by the stories that lie within.

MH: “Palestine Boy” follows a teenage immigrant to the United States fleeing violence in the West Bank. His family are goat farmers and he’s joined the track team. It’s in running that he seems to find solace from all his fears and feelings of conflict about being safe in America, while his cousins continue to live in danger in Palestine. A lot of your other stories also follow runners. Narratively, what does running provide for you as a writer?

LR: As you might have guessed, I’m a long-distance runner. It’s a meditative hobby. A little bit self-obsessive, as well. Sometimes even self-destructive. Runners make sense to me. There’s something innate about wanting to run ten miles just because one can. But it’s also kind of ridiculous. I often use running as a way to highlight a character’s internal conflict.

Chances are, when I think of a character as a runner, I imagine they have unresolved issues of the self.

MH: What does the title story, “Impossible Naked Life,” say about a reality TV show shaped around surviving the wilderness while naked, say about all the other pieces in this collection? Do you believe there is an emotional or metaphorical thread that begins here and can be traced throughout the collection?

LR: We can’t hide from our nakedness. Once we are unmasked, we are who we are. And the impossibility of life is something we come to grips with on a daily basis. That title felt right for this piece, and the collection as a whole.

There’s a duality, I think, in this collection—the real and the surreal competing for space. When I think about the book in its totality, I think about how it tries to live in the boundaries between those realms.

MH: What’s next for Luke Rolfes?

LR: I’m excited to have a novel coming out in early 2024 from Braddock Avenue Books called Sleep Lake. I’ve been writing more short stories and flash fiction, and I’ve also been working on a new novel manuscript which centers around an old amusement park. I don’t know yet if it will go anywhere, but I am having fun with it.

Impossible Naked Life (176 pages) is available from Kallisto Gaia Press.

__________________________

Luke Rolfes is the author of two story collections, Flyover Country (Winner of the Georgetown

Review Press Short Story Collection Contest) and Impossible Naked Life (Winner of the Acacia

Prize), and his stories and essays have appeared in numerous journals. He teaches creative

writing at Northwest Missouri State University and edits Laurel Review.

Maitlyn Harrison studies creative writing at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock and

recently served as an editorial intern at AY Magazine.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.