The following essay by Jolene McIlwain is part of SmokeLong Quarterly’s series on Flash in the Classroom, in which we invite instructors to share how they use flash fiction. If you’re an instructor who teaches flash, we’d love to hear about your experience. Submit your essay HERE.

____________________________

by Jolene McIlwain

I love literary analysis and literary theory. I love writing and reading short shorts: micros, flash, sudden fiction. So, deconstructing short forms in the classroom has been an amazingly satisfying treat in my work at two Pittsburgh-based universities: Chatham and Duquesne. I’ve had the luxury of choosing the texts—unconstrained by required anthologies, length, genre, or author—and exposing students to recently published pieces by lesser known authors in lesser known journals as well as the well-known, well-worn anthologized pieces like Kate Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour” and Carolyn Forché’s “The Colonel.”

Flash can hit you emotionally, but it can hit you in more objectively quantifiable ways, too, when you take the time to deconstruct it. Here are six approaches I use when utilizing flash to teach students how to deconstruct and analyze texts:

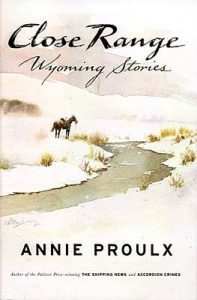

1. Close readings/Multiple readings. Understanding literary analysis and theory requires an investment from the students to enter the text multiple times, each time thoroughly searching for new details, inconsistencies, and possible meanings/readings, layering their analyses with more information. Flash is so short so one can analyze every single sentence, phrase, word without becoming too overwhelmed. Also, because flash comes in around the 1,000 word count or less, it’s uniquely set up to propel the reader to the end, leaving them asking for more, as in Annie Proulx’s “55 Miles to the Gas Pump,” a micro from CLOSE RANGE about a serial killer found out after his wife’s snooping in the attic, which ends with the line: “When you live a long way out, you make your own fun.” I’m not suggesting a twist or shocking ending is required, though some flash offers that. Sometimes readers are left saying, “Wait! what?” They are compelled to go back to the beginning and reread the story, like hearing that nice click of a door closing and wanting to open it again, to revisit. Either of these scenarios is a literary analysis or theory teacher’s dream. You don’t have to tell the student to reread it—you know they will. A favorite I teach for both Marxist and popular culture theories is Ian Frazier’s “Tomorrow’s Bird,” (originally published in Harpers, reprinted as “Count on Crows” at UTNE). The ending reads like a marketing slogan. A close re-read will expose all the sales language missed.

1. Close readings/Multiple readings. Understanding literary analysis and theory requires an investment from the students to enter the text multiple times, each time thoroughly searching for new details, inconsistencies, and possible meanings/readings, layering their analyses with more information. Flash is so short so one can analyze every single sentence, phrase, word without becoming too overwhelmed. Also, because flash comes in around the 1,000 word count or less, it’s uniquely set up to propel the reader to the end, leaving them asking for more, as in Annie Proulx’s “55 Miles to the Gas Pump,” a micro from CLOSE RANGE about a serial killer found out after his wife’s snooping in the attic, which ends with the line: “When you live a long way out, you make your own fun.” I’m not suggesting a twist or shocking ending is required, though some flash offers that. Sometimes readers are left saying, “Wait! what?” They are compelled to go back to the beginning and reread the story, like hearing that nice click of a door closing and wanting to open it again, to revisit. Either of these scenarios is a literary analysis or theory teacher’s dream. You don’t have to tell the student to reread it—you know they will. A favorite I teach for both Marxist and popular culture theories is Ian Frazier’s “Tomorrow’s Bird,” (originally published in Harpers, reprinted as “Count on Crows” at UTNE). The ending reads like a marketing slogan. A close re-read will expose all the sales language missed.

2. Gaps. Lovely gaps. Word count requirements force the author to leave much out. Literary analysis thrives in the gaps, in the ambiguity. It’s where the reader climbs into the text to figure out what it means, which emotions it taps into; they gain a sense of mastery by puzzling it out. Gaps can lead to outside research where the reader is driven to look up obscure phrasing or perhaps other works by the author in their search of connections, recurring themes.

One of the most appealing aspects of flash is that there is no room for large swaths of explanation, back-story, history. The author must cut extraneous details—and the elements they keep gain greater importance. In “The Colonel” a piece set in 1978 El Salvador, the unnamed daughter files her nails. Why does Forché include that detail? What’s left out is equally—if not more—important in literary analysis. In flash, setting can be hinted at more than explained (in “The Colonel” there’s a maid, a commercial in Spanish). Authors can bring characters to life with minimal description—sometimes, strategically, without names as in “The Colonel.” Also check out David Foster Wallace’s “Incarnations of Burned Children” and ask yourself why he chooses not to name the parents, the baby.

3. Voice, tone, POV. These come into play especially with psychoanalytic theory. Choosing POV, creating tone, establishing voice through word choice, word count, etc., all greatly affect the reader’s experience. With psychoanalytic theory, again, we look at what is repressed/left out as much as we look at what’s there. In one class period, we can reimagine and rewrite the whole story in another POV to see how this affects the message. What if Aimee Bender’s “The Rememberer” were told in all of the husband’s devolving voices? How might he see the human condition differently? Why does Leelila Strogov use the second person POV in her story “Paper Slippers” (why NOT first or third?) and what does the imagining part of the story reveal? (Psychoanalytic theory is big on imaginings and dreams.) Rewriting and reimagining is yet another way to enter the story.

4. Experimental/Hybrid forms. What is a story anyway and how can a list or a lecture or “fake” function as a story? Jamaica Kincaid’s “Girl,” Kathy Fish’s “Collective Nouns for Humans in the Wild” and “Lifecolor Indoor Latex Paints® – Whites and Reds” by Kristen Ploetz show that form is an essential part of the “telling.” The anthology, FAKES, includes stories written as multiple choice tests, police blotters, letters, etc., which can ignite great discussions on how form functions and how form can shape how we interpret stories. One such favorite is Michael Martone’s “Contributors Notes.”

4. Experimental/Hybrid forms. What is a story anyway and how can a list or a lecture or “fake” function as a story? Jamaica Kincaid’s “Girl,” Kathy Fish’s “Collective Nouns for Humans in the Wild” and “Lifecolor Indoor Latex Paints® – Whites and Reds” by Kristen Ploetz show that form is an essential part of the “telling.” The anthology, FAKES, includes stories written as multiple choice tests, police blotters, letters, etc., which can ignite great discussions on how form functions and how form can shape how we interpret stories. One such favorite is Michael Martone’s “Contributors Notes.”

5. Titles. Creativity in flash titles never ceases to amaze me. Take another look at the pieces I’ve mentioned thus far. Analyze how these titles enhance the stories, how these titles function in the stories. In Jim Heynen’s “What Happened During the Ice Storm,” the title asks, the story answers… But we can also count the number of times Heynen repeats some form of the word “ice” from the title (10) and consider how these words counter the warmth in the end.

For another example of a memorable title and a story in list form, take a look at Gwen Kirby’s piece “Shit Cassandra Saw That She Didn’t Tell the Trojans…” up at SmokeLong, a piece I plan to teach in the near future within my feminist, psychoanalytic, and pop culture theory units.

6. Repetition. I love to see the boldness of flash authors who use/exploit repetition even when held to a word count. We can count the number of times Peter Markus repeats a handful of words in “The Moon is a Star” or “Good, Brother,” and many of his works. The repetition creates tone, voice, character, atmosphere that help to focus us. Repetition alone does all the work!

With literary analysis and theory, we must look at the piece as objectively as possible, citing quantifiable numbers: How many times does the author repeat this word, motif, or consonant for effect/message? How many sentences are there? What is their length? Long? Short? In “Incarnations of Burned Children,” DFW writes just over 1,000 words in one eight-sentence paragraph. Why? Authorial choices such as this lead the reader to make assumptions on what we think the author wants us to notice.

If you write but don’t teach flash, consider, while revising, how a reader might climb into your piece and nose around. Write lines that welcome analysis, endings that compel the reader to re-read. Cut, cut and leave some work for your readers. They might love you for it! Play with titles, repetition. Try out fakes if you haven’t. Explore changing POVs. If you want to learn more about “reader-response” theory, see the work of Wolfgang Iser. For other theories, check out the text I’ve used for years, Lois Tyson’s Critical Theory Today. We literary theory and analysis teachers can’t wait to teach your work!

______________________________

![]() Jolene McIlwain’s work appears online at The Cincinnati Review, New Orleans Review, Atticus Review, Litro UK, Prairie Schooner, Prime Number, Fourth River, and elsewhere and has been selected finalist for the 2018 Best Small Fictions anthology, Glimmer Train’s Very Short Fiction contests, and the Arts & Letters Unclassifiables Contest, as well as semi-finalist for Nimrod’s Katherine Anne Porter Prize and American Short Fiction’s Short and Short(er) fiction contests. She’s an associate flash fiction editor at jmww Journal, and while taking a short break from teaching, she’s currently working on a short fiction collection and novel set in the hills of the Appalachian plateau in Western Pennsylvania.

Jolene McIlwain’s work appears online at The Cincinnati Review, New Orleans Review, Atticus Review, Litro UK, Prairie Schooner, Prime Number, Fourth River, and elsewhere and has been selected finalist for the 2018 Best Small Fictions anthology, Glimmer Train’s Very Short Fiction contests, and the Arts & Letters Unclassifiables Contest, as well as semi-finalist for Nimrod’s Katherine Anne Porter Prize and American Short Fiction’s Short and Short(er) fiction contests. She’s an associate flash fiction editor at jmww Journal, and while taking a short break from teaching, she’s currently working on a short fiction collection and novel set in the hills of the Appalachian plateau in Western Pennsylvania.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.