SmokeLong‘s “Flash, Back” series asks writers to discuss flash fiction that may be obscure or printed before the term “flash fiction” became popular, and tell us how these older or not widely-known works are meaningful. Writer and professor, Jacqueline Doyle, is the first in this series. She introduces the column by revisiting Jayne Anne Phillips’ Black Tickets and Sweethearts, and evaluating their subliminal influence on her writing. Submit your own “Flashback” or other flash-related essays on our Submittable page!

By Jacqueline Doyle

The spine of my mass-market Laurel paperback of Jayne Anne Phillips’ Black Tickets is broken, whole sections falling out, the paper brittle and yellow. A price sticker on the blue cover reads $3.95. On the flyleaf: my name and “Ithaca, July 1983.” I was back in graduate school at Cornell then, following a hiatus from my studies after my divorce. It was humid and hot. I had a summer scholarship and I was in love, spending a lot of time at my new boyfriend’s studio apartment downtown, long lazy days when I could read for fun. I don’t know how I described the very short stories in Black Tickets to myself at the time. It would be years before the term “flash” meant anything to me. My boyfriend was a writer in the MFA program, but I was working on a PhD, where we barely touched on contemporary literature. It would be years before I became a writer myself.

That summer I was also reading Edgar Allan Poe for my dissertation, who favored compression, the “short prose narrative, requiring from a half-hour to one or two hours in its perusal,” cautioning against “undue brevity” but even more against “undue length” (his own tales requiring less than half an hour to read). I was reading and re-reading “The Waste Land,” beguiled by T.S. Eliot’s juxtapositions of glittering fragments. I was reading Virginia Woolf, who predicted that women writers of the coming century would engage in new experimentation, introduce new subjects (particularly the unrecorded lives of women), produce books “adapted to the body” (“at a venture one would say that women’s books should be shorter, more concentrated, than those of men, and framed so that they do not need long hours of steady and uninterrupted work”). I was reading Adrienne Rich, who was “diving into the wreck” of old forms and outworn myths and emerging with new ones, and Audre Lorde, who proclaimed that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” Everything I was reading prepared me for what I was going to teach, and write about, and write myself in years to come, but I didn’t know that, stretched out on the green cotton blanket on my boyfriend’s double bed in front of the oscillating fan. Everything was fertile ground for my understanding of Jayne Anne Phillips, but I wasn’t thinking about that either. I only knew that her words jumped off the page and stayed with me.

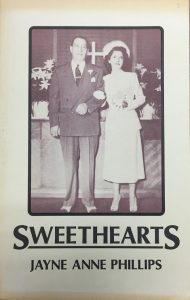

I might have called the opening story an ekphrastic vignette, if I’d been asked to classify it, though the word vignette suggests a marginal literary form, something slight. Not a portrait as powerful as “Wedding Picture,” which dives below the surface of the photograph it describes to explore the body “under the cloth” of the bride’s white wedding suit, what we can’t see or hear (“Her heart makes a sound that no one hears”), along with the history we can’t know. When “Wedding Picture” was included in The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Writing Flash Fiction in 2009, Phillips voiced her objections to the term “flash” (“there’s nothing flashy or spangled or shiny (superficial) about a great one-page fiction”), but also expressed her conviction that such fiction rivals other genres in importance. “The successful one-page fiction is a whole story in a paragraph or three: just as strong, tensile, and whole as the well-written story, novella, novel.”

I didn’t know at the time that Black Tickets originated in a flash chapbook (Sweethearts, from Truck Press, which I’ve miraculously unearthed in the Special Collections of my university library). But I did sense that the 16 very short stories were somehow primary in Black Tickets, not just secondary to the 11 longer ones. John Irving in his New York Times review didn’t agree. He called them “miniatures” (descriptive, but also dismissive), and “ditties” (not descriptive at all, and derogatory). His largely positive review was suffused with sexist condescension, starting with repeated references to “Miss Phillips.” (Surely not all female writers in 1979 were called Miss X? Or maybe they were. The first volume of the Norton Anthology of American Literature back then included only one woman, Emily Dickinson, whom the critics all called Emily, though male writers were referred to by surname.) Irving opened his review: “Of the almost 30 short fictions collected here, there are about 10 beauties and 10 that are perfectly satisfying and then there are 10 ditties—some of them, single paragraphs—that are so small, isolated and mere exercises in ‘good writing’ that they detract from the way the best of this book glows.” He didn’t discount all of Phillips’ short fictions (“I don’t want to suggest that all of her smaller pieces are ‘ditties’”), but expressed the hope that she’d write a novel.

The Great American Novel, the bigger the better! Phillips has obliged by writing a number of great long novels, but no female writers have been credited with writing the Great American Novel, which is surely a male provenance, even a reflection of the expansive imperialism of American manifest destiny. In a craft essay in Brevity, Joy Castro echoes A Room of One’s Own and Tillie Olsen’s Silences when she draws attention to privilege and the Great American Novel: “Every time we praise a literary book for its heft, we contribute to a kind of aesthetic confusion. The sheer length of a text is not a mark of its literary excellence or worth. Rather, it’s a reflection of the material conditions of the author’s life.” She herself began writing flash, she says, when she was a single mother struggling to make ends meet, living below the poverty line, overwhelmed by student loans and the demands of childcare. “Short forms,” Castro writes, “especially flash forms—are particularly amenable to writers snatching time from obligations. Such writers by definition include family caregivers, who continue to be mostly women, and people from poverty and the working class.”

This time around I’m reading Black Tickets as a writer, and paying particular attention to the flash. The narrative point of view varies (first person, third person, first person plural), but all of the narrators and protagonists in the flash fictions are female, most of them below the poverty line, most of them adolescent and preadolescent girls, “white an dewy an tickin like a time bomb.” They sleep together, drink together, read movie magazines together, go to matinees, tell pornographic and scary stories, sing along with the radio, flee boys, take care of their fathers. A stripper gives her fifteen-year-old cousin advice about appealing to the clientele. “With that long blond hair you can’t lose. An don’t you paint your face till you have to, every daddy wants his daughter.” A junior high girl pregnant by her brother, ostracized at school and at home, dismembers her unwanted newborn. “Next morning she sits in the house alone while the others shout and sweat at a revival in Clinger’s Field. The dogs come in with pieces in their mouths.” In “What It Takes to Keep a Young Girl Alive,” a girl with a summer job at a theme park watches as a body is carried out of her dormitory: “One day they carried a girl out of the barracks wrapped in an army blanket. They found her in the showers. Sue saw her rounded buttocks sag the olive wool. Inside there she was sticky.” The collection ends with a longer story narrated by a male serial killer. What does it take to keep a young girl alive?

The flash are both spare and rich, image-driven and rhythmically complex, the language lyrical, but also raw and visceral. In her Field Guide essay, Phillips draws attention to the radical compression and subversive potential of flash: “I didn’t realize it at the time, but I taught myself to write by writing one-page fictions. I found in the form the density I needed, the attention to the line, the syllable. I began writing as a poet. In the one-page form, I found the freedom of the paragraph. I learned to understand the paragraph as secretive and subversive. The poem in broken lines announces itself as a poem, but the paragraph seems innocent, workaday, invisible.”

Irving let his critical guard down and unwittingly exposed himself when he wrapped up his New York Times review with the line, “This is a sweetheart of a book.” The context makes his compliment potentially comic. He’d even quoted the relevant passage from Phillips’ flash “Sweetheart,” undaunted by the fact that it’s a dirty old man who hugs the preteen girls and calls them sweethearts: “Stained fingers kneading our chests, he wrapped us in old tobacco and called us his little girls. I felt his wrinkled heart wheeze like a dog on a leash. Sweethearts, he whispered.”

It’s a warm hazy day in September when I drive into campus to look at Phillips’ chapbook Sweethearts, by appointment, in the Special Collections Room at our library. A California State University campus with overtaxed faculty, low income students, and a drastically waning budget, we don’t have the kind of library that houses special collections, or even many books published in the last couple of decades, so I’m surprised and gratified to discover Sweethearts, long out of print. Classes don’t start for a week, and the campus is deserted, apart from workers in hard hats drilling in the parking lots and raising dust in the library courtyard.

The 1976 chapbook from Truck Press in North Carolina is off white, yellowed at the top and bottom, with the sepia wedding photo described in “Wedding Picture” on the cover. I sit down and read the entire collection, 24 flash, none more than a page, 13 of which made their way into Black Tickets in 1979. It takes me a bit over half an hour, well within Poe’s parameters for the ideal prose narrative. In Black Tickets, the flash are amplified by the longer stories, which explore male as well as female characters (often pairs of middle class daughters and mothers). The men are sad and divorced, old and sick, angry and violent. Reading Sweethearts is a different experience, focused more on the private world of young girls. “Chloe likes Olivia,” Woolf observed of the fictional Mary Carmichael’s experimental novel, imagining fiction in the future that would focus on women in relation to each other and not solely in relation to men. “We lay on a cot pretending we were Troy Donahue and Sandra Dee, touching each other’s stomachs and never pulling our pants down,” Phillips writes in “Stars.” “The Lettermen did billowing movie themes. There’s a summer place, they sang. Where our hearts. Will know. All our hopes. She put her face on my chest. You be the boy now, she whispered.” Summer over, the other girl writes letters to the ten-year-old narrator. “Just because you’re a year older than me, her last one said, is no reason not to answer.” Sweethearts vibrates with the energy of the girls’ intimacies and betrayals. I love reading the flash gathered together on their own.

Rereading Black Tickets and reading Sweethearts for the first time has been a revelation. I’ve kept up with Phillips’ novels, even taught Machine Dreams, but I haven’t thought about Black Tickets for years, or about the graduate student lounging in front of the fan during that hot Ithaca summer, innocent of her future. Pressed to name a literary influence on my upcoming flash chapbook The Missing Girl, I might have said Joyce Carol Oates, maybe Sherwood Anderson. But now I wonder whether Jayne Anne Phillips played a greater role, both her formal innovations and her themes and sensibility, even though I was unconscious of it. The effects of my first introduction to flash may have lingered and reverberated for over thirty years.

The one-page story continues after the last line, according to Phillips. “Fast, precise, over. And not over.”

Jacqueline Doyle’s flash chapbook The Missing Girl (forthcoming from Black Lawrence Press in 2017) won the Black River Chapbook Competition. She has published flash in Quarter After Eight, [PANK], Monkeybicycle, Sweet, Café Irreal, The Pinch, Nothing to Declare: A Guide to the Flash Sequence (White Pine Press, 2016), and many online journals. Her creative nonfiction and fiction have earned two Pushcart nominations, a Best of the Net nomination, and two Notable Essay citations in Best American Essays. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with her husband (the MFA with the studio apartment) and their son.

Jacqueline Doyle’s flash chapbook The Missing Girl (forthcoming from Black Lawrence Press in 2017) won the Black River Chapbook Competition. She has published flash in Quarter After Eight, [PANK], Monkeybicycle, Sweet, Café Irreal, The Pinch, Nothing to Declare: A Guide to the Flash Sequence (White Pine Press, 2016), and many online journals. Her creative nonfiction and fiction have earned two Pushcart nominations, a Best of the Net nomination, and two Notable Essay citations in Best American Essays. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with her husband (the MFA with the studio apartment) and their son.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.