by Jess D. Taylor

It briefly felt like the exact wrong move—to kick-start my college lit class with a flash about a blow job. Sure, the topic is seductive and the context somewhat subversive, both easy attention-grabbers, but the reason I like this story is for its subtlety. At first blush, many readers don’t even realize someone’s been fellated.

Under normal circumstances, my junior college classes are filled with freshmen and sophomores, mostly young but several who’ve grown out of teenage-hood into various stages of adulthood, some even older than me. But on this particular scorching August day, my first time teaching at the more suburban satellite campus of my local community college, I heard myself reading “he stiffened accordingly…” aloud to a room filled with the smooth, terrified faces of high school junior overachievers. My gut went cold. The silence was thick.

Luckily, it didn’t take long for them to jump right into the blow job story, “The Rumor Was,” which starts with an image of decapitation on a roller coaster and ends with the final orgasmic drop from “the top, where he threw his hands up and screamed.” What happens in between is that the guy thinks he’s gonna cop a feel but his date actually “initiated acts with her mouth he had not expected.” He’s thrown off: “Was he to lay back, to moan, to fill his eyes with the moon? Like a girl?”

In less than 500 words, author Kara Vernor catapults us into a consideration of patriarchy, power, gender norms, and narrative control. My students are familiar with these abstractions, of course, but now they’re lit from within, agents rather than receptors, debating why in the aftermath our guy “didn’t mention his banging heart, a car loose from its track.”

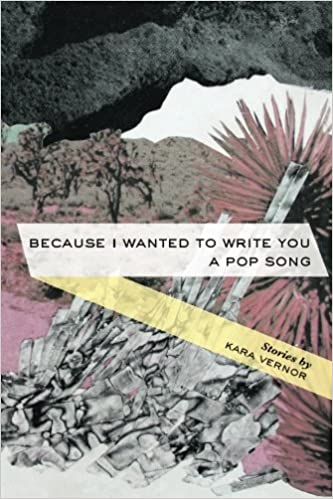

This is why I can’t stop teaching Vernor’s slim collection of flash fiction, Because I Wanted to Write You a Pop Song (Split Lip Press, 2016), though its subject matter seems riskier than ever. As some professors are abandoning potentially provocative “triggering” material, fearing student fragility and backlash, I’m compelled to continue challenging my students to be made uncomfortable (not, to be clear, made unsafe).

Semester after semester, I watch as they get thrown off by Vernor’s fresh, wry prose and then work to regain their footing in unfamiliar terrain. They’re initially delighted at the brevity of flash and then intimidated at how densely packed it can be. Students are compelled to read deeply more than swiftly, marveling at how the words do such heavy lifting. They become invested in metaphor and mechanics, like point of view, as they identify unreliable narrators who are oblivious to their own mediocrity, insanity, and even sexuality.

Violence both explicit and implicit charges several of these flashes in ways that are provocative, but never merely gratuitous. In “She Could Maybe Lift a Car,” the female narrator enters a party covered in her boyfriend’s blood after an altercation in which he said she looked “a little slutty” and pushed her to the ground. In retaliation, “her heel snapped his nose and it sounded like a plum splattering.” But Vernor doesn’t land on some easy note of girl-power, nor does she glorify her narrator who, after cleaning herself up, says, “I look ready to open the door to a house full of guys I haven’t yet dated.” Students volley between criticism and compassion, a nice segue into examining why we make allowances or not for certain people and circumstances.

Other stories bury the implication of violence in subtext and we haggle over what is meant by a single line or reference. Is there enough evidence, for example, to convict the date in “Prom Queen Found In Lake” who sings Mick Jagger out of the open roof of their limo and whose “fingernails bit into her nape” while slow dancing? A line like “At the dance she was the sun and he was a planet in need of heat” leads to rich considerations of adolescent relationship dynamics and more broadly, toxic monogamy culture—a framework many don’t even realize they’ve unconsciously adopted.

Vernor does not shy away from the ugliest parts of adolescence, exploring parental neglect, mental illness, drug use, and even sexual abuse with an unsentimental frankness that open chasms of emotional depth. In “Bonus Round” the narrator sees her molester, now “a deflated balloon,” on Wheel of Fortune, decades after he touched her while talking of his new sailboat. The spinning wheel stopping just short of Bankrupt serves as a clever metaphor for how justice is not always served. And though the narrator’s suffering has manifested in self-destruction over the years, she’s also learned to live with and not be singularly defined by her trauma—which is a refreshing narrative for many students who’ve absorbed the messaging that we are the sum total of everything bad that’s happened to us.

The potent truths embedded in Vernor’s stories can feel taboo, even illicit; it’s not uncommon to walk into class and find discussion already underway. By the time we get to “Visitor, Transistor,” in which a bored video store clerk has an unexpected and not negative encounter with a trench coat-wearing man, whose “breath on [her] neck is a jungle,” the students are used to disorientation. They aren’t sure if this is real or fantasy, which is partially the point. Vernor’s writing reminds us that literature registers viscerally, emotionally, and intellectually—and sometimes those reactions are at odds with each other. Resist the impulse to worship at the altar of fundamentalism, I often tell my students, for most of life is lived in messy, nuanced gray areas. Class time drains quickly as they sink deeper into the muck of their conflicting reactions, raising new questions as they answer old ones.

The overwhelming majority of students echo the sentiment that this is exactly the kind of literature they’ve been hungry for (despite having been convinced that they had no appetite). Some do point out certain limitations—the absence of racial identity in most of the characters, the lack of intersectionality. Their concerns are both a testament to the (laudable) mainstreaming of equity and social justice, and a great opportunity to discuss the expectations we put on literature. Must everything we read check all the boxes of inclusiveness? What are the benefits and limitations of, say, paranoid reading versus reparative reading?

Because I Wanted to Write You a Pop Song continues to find its way onto my syllabus, though subject to ever-evolving frames, pairings, and essay prompts. I’m not the only one who’s taken notice; W.W. Norton is anthologizing “David Hasselhoff is From Baltimore” in its 2023 flash fiction anthology. That story, which closes the collection of 21, might just be my favorite. Written in second person, it’s about a woman who comes to California in search of she knows not what. It’s a tall order, to abandon surety and trust the unknown—and yet, as my students have come to realize, it’s one of the reasons we read fiction to begin with. “An oncoming wave readies to bury your head,” Vernor writes, “and your arms butterfly forward, your feet kick free of land.”

_________________________

Jess D. Taylor’s writing has appeared in The Dillydoun Review, 100 Word Story, Creative Nonfiction’s Sunday Short Reads, Wraparound South, Little Patuxent Review, Pidgeonholes, Traveler’s Tales, and elsewhere. She teaches college English and raises her two daughters in Santa Rosa, California.

Jess D. Taylor’s writing has appeared in The Dillydoun Review, 100 Word Story, Creative Nonfiction’s Sunday Short Reads, Wraparound South, Little Patuxent Review, Pidgeonholes, Traveler’s Tales, and elsewhere. She teaches college English and raises her two daughters in Santa Rosa, California.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.