by Kelly Lynn Thomas

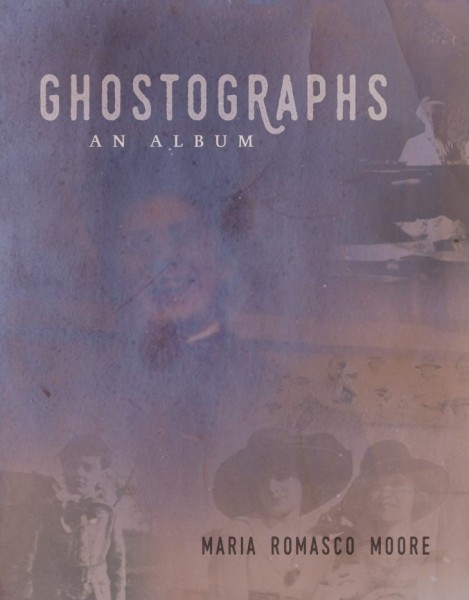

In Maria Romasco Moore’s debut collection of flash fiction, Ghostographs: An Album (Rose Metal Press, 2018), vintage photos serve as the jumping off point for stories that subvert and redefine our conceptions of light, time, and life—what they are, what they do, and what they mean for us and our experiences.

Ghostographs follows an artificial constraint—each story is inspired by a photograph that appears alongside the text—but it does not feel restricted or stunted. Rather, Moore’s prose enlivens and complicates each photograph, often taking the visual reality presented in an unexpected direction. Although not without flaws, Moore’s stories are delightfully unnerving without being creepy or feeling gimmicky.

For example, the photo that accompanies the story “Tess” is an over-exposed image of a young girl who looks like she is glowing, and indeed, the story is about a girl who glows so brightly it hurts to look at her. In “Lewis,” a group photograph of women standing in a field of tall grass inspires a story that transforms the women into beings that grew from the ground like any other plant. A photo of a woman holding a child atop a mailbox becomes a story about a defective mail-order baby in “Hannah.”

While the vintage photographs range in subject matter, most contain people, and many contain spots of unnatural brightness or areas of overexposure, revealing Moore’s likely inspiration for her exploration of light. She reveals in the author’s note that most of the photographs came from yard sales or flea markets.

It’s unlikely the images share anything aside from their age, but the author stitches them together into a cohesive whole by using the same narrator throughout. Presumably a child, the narrator acts as an observer of the strange town in which they live, but also as a repository for accumulated wisdom about the town’s more fantastical elements.

The narrator, who is never named, explains what her grandfather taught her about light in “Different Kinds of Light,” which is paired with a picture of a cat sunbathing. “You’ve got to be careful with light, he told me. Some of it is shadow in disguise. Some of it isn’t light at all, merely the absence of darkness. Some of it can burn you. Some of it is colder than ice. Ice casts a light, as does stone. Some light is dangerous. Some light is safe.”

Photographs, are, of course, light that is captured and held in stasis, forced into one never-changing form. And light, as the narrator points out too often, is tricky. But so, too, are these stories.

Ghostographs opens with a single line of text positioned beneath a cut-off photo: “Every story is a ghost story.” The photo, bifurcated by the book’s binding, takes up only a quarter of the two-page spread. It shows a sepia-toned image of a group of men dressed in white, faded and ghostly. The taller men’s heads are cut off by the physical ending of the page.

Two pages later, the narrator—or perhaps the author, it is unclear—explains further that “The truth of it is that every single instant, we are, all of us, obliterated and refreshed.” This means that we are all ghosts of our previous selves, and all stories are therefore ghost stories. “These are mine,” the narrator tells us, before we turn the page to the first story.

“The Woman Across the Way” feels more like a vignette than a true story, but it does serve the reader as an entrance point to this strange world of living light and shadow. The opening line, “Underneath her skin there were snakes,” shows us that while the narrator uses the word “ghost” more as a metaphor for constant change than death, she is doing so in a world where the impossible has become possible. The choice of snakes imparts a sense of danger that only grows in the second story, “The Bridge Over the Abyss.”

The photograph paired with this story is one of the darker ones in the book, almost completely consumed by shadow. A woman in a hat stands at the end of the bridge, her facial expression inscrutable. Unlike many of the stories in Ghostographs, which make characters directly from their photographs, this woman is not mentioned. She is a ghost in the sense that we see her there, but know nothing about her. For all we know, she could be the abyss.

Moore’s flash fiction stories are skillful compressions that use specific language to great effect, although “The Woman Across the Way” is far from the only one that feels more like a vignette than a complete story. Even so, the rhythm of Moore’s sentences and the precision of her descriptions carry the reader through. With the exception of the preface, each flash story takes up no more than a page, and many of them require only half a page.

The real talent, and what makes this a fun, playful exploration of image and text instead of a pretentious affectation with no real depth, is how Moore strings the collection together. Ghostographs reads like a more mysterious version of the classic novel-in-stories Winesburg, Ohio by Sherwood Anderson. Throughout the collection, characters appear and disappear and reappear, always changed in some (often sinister) way.

“And like the flicker of a shutter, light remakes us every instant. Every bird. Every leaf. Every ripple on the surface of the river. You. Me,” the narrator observes in “Light,” the second-to-last story in the collection.

It’s this change and ultimate erasure of the town and its inhabitants that makes the collection work. Characters morph physically and emotionally, they die and are reborn, they are forgotten and swallowed by the abyss. Moore presents them as ghosts of the moment, and brings this point home as she shows us subsequent snapshots of their lives.

We are our own ghost selves, past, present, and future, these photographs and stories say. How will we be remembered?

_____________________________________

Kelly Lynn Thomas reads, writes, and sometimes sews in Pittsburgh, PA. She lives with her partner, one dog, and a constant migraine. Her fiction has appeared in Permafrost, Sou’wester, The Journal of Compressed Creative Arts, and was nominated for a 2017 Pushcart. Kelly received her MFA in Creative Writing from Chatham University, is a coordinator for the VIDA Count, and can always be found with a large mug of tea.

Kelly Lynn Thomas reads, writes, and sometimes sews in Pittsburgh, PA. She lives with her partner, one dog, and a constant migraine. Her fiction has appeared in Permafrost, Sou’wester, The Journal of Compressed Creative Arts, and was nominated for a 2017 Pushcart. Kelly received her MFA in Creative Writing from Chatham University, is a coordinator for the VIDA Count, and can always be found with a large mug of tea.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.