by Emily Webber

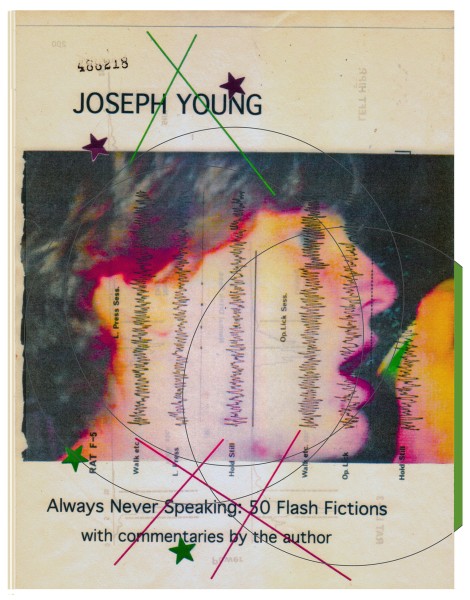

Always Never Speaking: 50 Flash Fictions, with Commentaries by the Author by Joseph Young (RowHouse Press, 2019) gives voice to dreamers and drifters and people just trying to get by in life. It offers the reader a voyeuristic view into conversations between strangers, friends, and loved ones. The voices populating these vignettes are like the best kind of people watching—overheard snippets of conversations that leave a person wondering about what they overheard long after. All of these stories are very short, offering a quick glimpse into a small moment of someone’s life. Most of these stories succeed, the few that don’t seem more like sketches—not giving the reader enough to care about. When Young pulls it off these stories are heart-rending and insightful. By putting these intimate conversations on the page, Young shows how people search for signs in the world around them, where people find hope, and how when people get lucky, they can find a moment of magic in ordinary interactions with others.

At the end of each story, there is a line of commentary offered by the author on flash fiction such as: Flash fiction’s white space is full of ghosts. Half of flash fiction is the absurd. Remember, in flash fiction dialogue sows confusion. These commentaries seem to say that flash fiction is everything and nothing. That rules should be broken, and that writing should involve play and experimentation. It is a good message and one that shape Young’s writing. He lets his stories run wild and he’s not afraid to experiment. But the commentaries, while they break up the many different voices encountered in this collection, serve mostly as a distraction and the reader is left trying to puzzle out the meaning before dipping into the next story. There’s no doubt that Young has an eccentric and unique approach to creating his art and a view into his creative process would be valuable but may have been more successful in a different format.

In the best of these stories, Young is not afraid to show the reader the dull moments, the moments of despair, but mixed in are brief flashes of grace and a hint of something beautiful. In “Cat,” two former lovers have a chance meeting in a park. At first, it doesn’t go well, but then:

“Ha!” she said, tossing her hair. “Of course it is.” I followed her eyes as she looked out over the park lawn, bright with hundreds of dandelions. The clouds running overhead threw patterns of warm, deep light onto the ground. Then she turned back to me and smiled. “Hi, Paulie,” she said.

In 2018, Young installed text on the surfaces of his home to tell the story of a fictional family that lived there, and these stories deliver something similar. It is as if the reader is looking in on someone’s home, a glimpse into their lives. Young crafts beautiful sentences that beg to be read out loud and are paired with startling images, often bringing in the landscape that the characters inhabit. The story “Simple” is only a little over than ten sentences long, but Young manages to evoke a feeling of both longing and indecision between two people in language that surprises: “She turned away, tasting the snowflake on her lip. And all this, she thought, the dirt frozen in the roots of a fallen tree, the open ice of the lake. They stood that way in the quiet, backs to one another. The simple blue of the woods crept toward them.”

Young also understands people and what gets in their way. A character in “Twelfth Night” vows to look at things differently, but he says: I could already feel reason piling dust on my heart. In the stories “The Day’s Surge,” and “Found,” and “Empty Room,” Young masterfully conveys how people try to keep each other safe in the world and how we find comfort. In another story “Safe” a young boy longs to tell his beloved brother that he can fly. Young uses beautiful images to capture the spirit of a boy trying to understand his world and break free: “There was plenty of room between its warm, upward arms, 50 feet up. He floated among the leaves, brushed them softly with his feet and hands, surprised the birds with his silence. He wanted to rise above, into the unfettered blue, but he wasn’t sure. What would happen should someone see him?”

“Rainbow Joke” ends with the following lines: He sat on the porch and watched the people go by. Such a big place, he said, such a funny world. This sums up Young’s collection well. Spending time with the people that populate Young’s 50 flash fictions show what a wonderfully weird world this is, and that there’s magic to be found even in the most ordinary of moments.

_________________________________

Emily Webber was born and raised in South Florida where she lives with her husband and son. She has published fiction, essays, and reviews in the Ploughshares Blog, The Writer magazine, Five Points, Maudlin House, Split Lip Magazine, and elsewhere. She’s the author of a chapbook of flash fiction, Macerated, from Paper Nautilus Press. Read more at www.emilyannwebber.com.

Emily Webber was born and raised in South Florida where she lives with her husband and son. She has published fiction, essays, and reviews in the Ploughshares Blog, The Writer magazine, Five Points, Maudlin House, Split Lip Magazine, and elsewhere. She’s the author of a chapbook of flash fiction, Macerated, from Paper Nautilus Press. Read more at www.emilyannwebber.com.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.