The envelope in the mail from Daddy had twenty dollars in it and a sentence scribbled on a cocktail napkin that still bore the impression of his glass. He wanted another visit.

It was late February. Cold. The snow on the sidewalks had been there and been there. Dirty layers marked the winter’s passing like tree rings. Me and Irene and Kevin, trekked up the hill to the bus stop in so many layers of flannel and wool that we all but lost the use of our movable parts. Mama and Daddy separated for good last summer, but he didn’t ask to see us until December, so our visits were made in boots and leggings and scarves and hats and merciless layers of sweaters, each one donned obediently under the eye of the hawk—Irene.

The bus ride to Daddy’s was an endurance test. The heat had one setting: intense. So for half an hour Kevin and I sat as close to the accordion doors as we could and prayed for someone to flag the bus down or get off at the next stop so we could feel some air against our cheeks.

The visits weren’t fun. We never laughed. We hardly spoke. He’d forget we were coming and answer the door wearing the undershirt he’d slept in. Later he’d speak through the smoke of his Camels to ask us how we were doing, so we’d make stuff up. We watched TV and he gave us popcorn, but not always. Sometimes he had licorice, and we’d dig out tiny bits of it from our cavities all the way home on the bus.

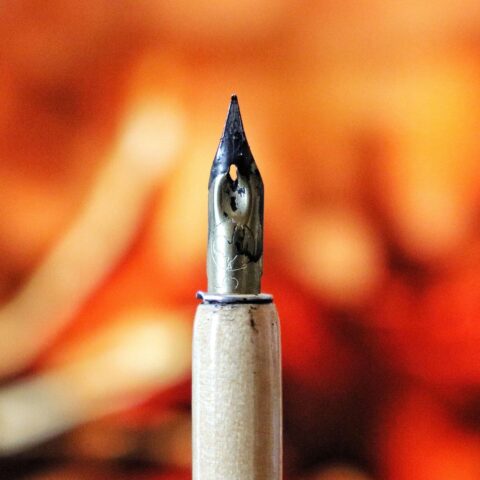

That day he took us to the Mapes Tavern for hamburgers and potato chips. We had to walk several blocks in the cold to get there, wind ripping across the side streets. I didn’t mind the walk because we’d pass the old book store on Tremont Avenue that had my pen in the window—the Parker fountain pen with the gold nib, like the one my teacher had.

I ran ahead of the others to look in the window. The light against the glass turned it into a mirror. I hated mirrors, mostly because they were so uncompromising about what I looked like. My hair was thick and straight, uncurlable and totally disobedient. My eyes were green but small and sad. Everything about me was small. I touched my chin, a receding little lump that offered no dignity. When there was no mirror around, I could pretend my profile was perfect and my hair glorious. I brought my face closer to the window to see the pen and be rid of my reflection.

Daddy’s giant silhouette came up behind me, with Irene and Kevin beside him. He was very tall, though he never seemed to be standing his full height, always slouching or leaning. He had wide shoulders and the slim waist of a man half his age. Sometimes I thought he was handsome, when he wasn’t angry. “What are you looking at?” he said.

“The Parker pen. It’s beautiful,” I said.

“I bet you’d like to have that one for your poems,” he said. He knew I would. It was no secret. I’d told him how much I wanted it every chance I got. He put his hands into his trouser pockets and jingled his change. The wind took his graying hair this way and that, mocking the swagger of a pose he was trying so hard to strike. “Well, suppose I send your mother the money next week to buy it for you?” He glanced at Irene to see if he’d made an impression. But she was hard; Irene had no patience for fantasies.

We walked back down our block late that afternoon with a big orange sun setting in between the long shadows of the apartment houses at the bottom of the hill—at least Irene did. I flew down, sliding behind Kevin along every patch of ice. When we reached our building, Irene called after me again, saying not to get my hopes up. But I bolted up the five flights, tearing off layers as I climbed, and found Mama ironing in the kitchen. I couldn’t get the words out fast enough. “Daddy’s buying me the pen. The Parker fountain pen, the one in the bookstore window. He’s sending the money next week.” Mama hardly caught a word, so I told her again.

“Well, that’s wonderful,” she said, but she didn’t seem to be listening; she was concentrating on a sleeve. Irene came in and gave Mama a look.

“That pen is six dollars,” Irene said.

I could see Irene didn’t believe he was buying any pen. Neither of them did, and I was afraid they would jinx it before it had a chance to happen. I left them, went into the bedroom. I took my leggings off, threw them into the corner, remembering too late that my ship was still in the pocket. He’d made it for me at the tavern, folded a paper napkin into a sailing ship, a toothpick for a mast. He put it on the bar when he was finished, told me it was magic, whispered in my ear. “This will take you anywhere you want to go,” he said, and pushed it gently along the bar. I stood eye level with it and watched it journey behind the bar’s rim—a smooth, dark wave—to a spot where the stubborn early-afternoon sun had pushed itself through the tavern’s tiny square window, a prisoner’s cell of a window, and lit the fragile sail.

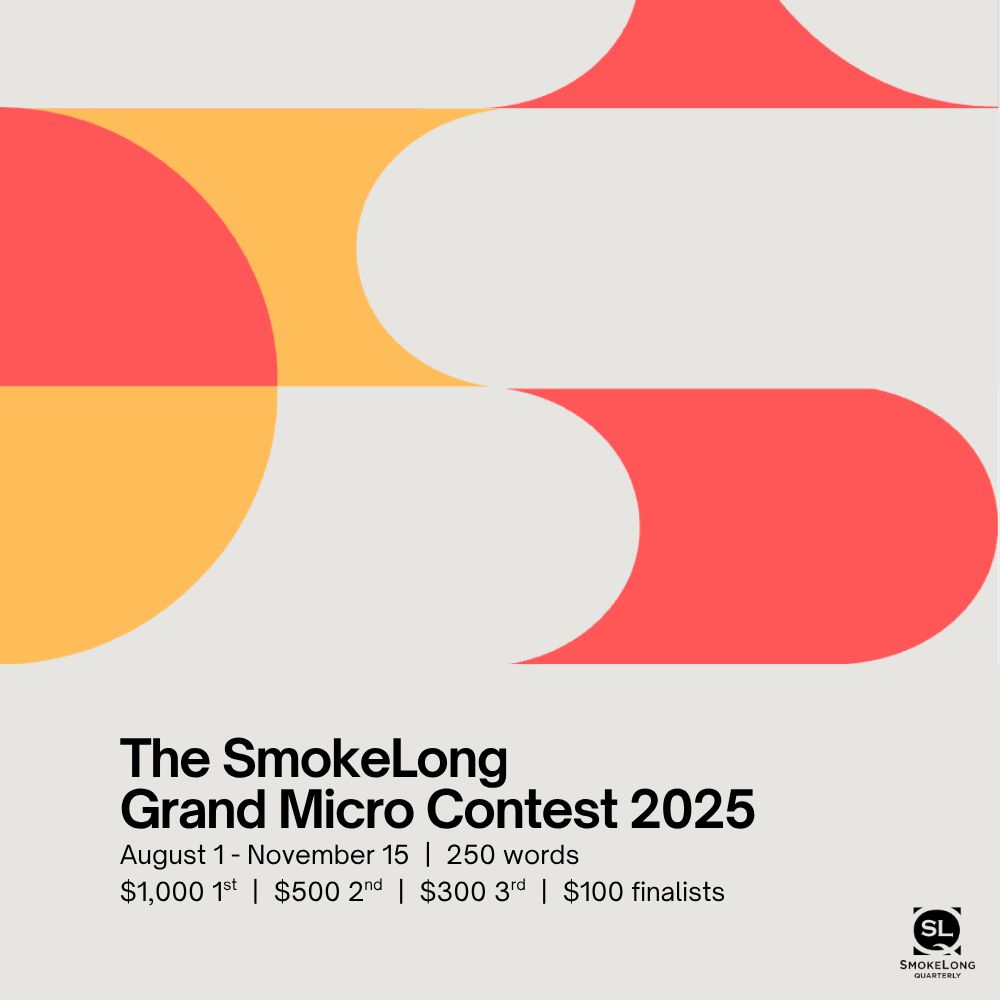

The SmokeLong Grand Micro Contest (The Mikey) is now an annual competition celebrating and compensating the best micro fiction and nonfiction online.

The SmokeLong Grand Micro Contest (The Mikey) is now an annual competition celebrating and compensating the best micro fiction and nonfiction online.