One of the things you do in your work that I find really interesting is that you blend real and imagined place. How much do these real and imagined places influence how you create characters? How do these settings help shape their sense of selves for you?

I tend to use settings as limiting factors to character motivations and reactions to various situations or triggers. Those grown in semi-insulated vessels and controlled environments, for example, would be laden with a set of biases and instincts that are different from those raised and set out in the natural world. Settings—both real and imagined—can also be reflective of a character’s inner turmoil or the lack thereof.

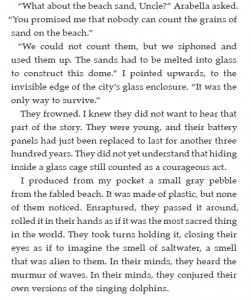

In Age of Blight, the undead character Beth has to have her bedroom emptied of furniture that might injure her. It’s because she won’t heal when injured. This is a character whose setting has been customized according to her needs. Setting can also be used this way: characters configured according to the setting. In the story “The First Ocean” in Age of Blight, I made the narrator exaggerate and lie a bit to satisfy a younger generation who had grown nostalgic for the long-gone sea.

I believe that a character existing in true vacuum, a character not saddled with the constraints of space or time and not burdened by history or the natural impulse to create a future that is an improvement of the present, is going to have a pretty boring story. There has to be a baggage somehow. Real and imagined geographical location, as well as time, could serve as baggage.

A story from your new collection, Age of Blight, that I like a lot is “There’s No Relief as Wondrous as Seeing Yourself Intact.” The description of the Empty from the man’s yellow organ to the spreading Empty on Carlos’ head. I feel like the Empty ties into so many different levels of discomfort and body anxiety: an unstoppable disease, a disease that can’t be hidden from others, and the sense for many people that because of the way The Empty works (people completely disappear at its end) there’s nothing behind. Can you talk more about writing illness?

Thank you, Megan. I’m glad you liked it. The Empty, the disease that painlessly erases a person, was inspired by entropy in classical thermodynamics. The original title of that story was “The Leech” (it was re-titled by the editor to “There’s No Relief as Wondrous as Seeing Yourself Intact” so it matches the black-humorish vibe of the other pieces in the book) to denote the all-consuming ethics of thermodynamic disorder, an entity with no concept of morality and cannot be made to choose between right and wrong. The Empty just erases people in purely misanthropic fashion, and I thought it was a fitting end to mankind—that people simply disappear so that the whole planet can regain its footing after all the man-made damage inflicted upon it.

Thank you, Megan. I’m glad you liked it. The Empty, the disease that painlessly erases a person, was inspired by entropy in classical thermodynamics. The original title of that story was “The Leech” (it was re-titled by the editor to “There’s No Relief as Wondrous as Seeing Yourself Intact” so it matches the black-humorish vibe of the other pieces in the book) to denote the all-consuming ethics of thermodynamic disorder, an entity with no concept of morality and cannot be made to choose between right and wrong. The Empty just erases people in purely misanthropic fashion, and I thought it was a fitting end to mankind—that people simply disappear so that the whole planet can regain its footing after all the man-made damage inflicted upon it.

I project my anxieties and fears when I write about illnesses whether they are real or imagined—and especially when they’re imagined. In “Those Almost Perfect Hands,” the protagonist is a kid with a strange “disease” which makes his hands “come alive.” It is probably my fear of being powerless and losing control over my body that’s doing all the talking in that story. Then there’s “Jude and the Moonman,” my twisted version of a coming-of-age tale featuring a band of childhood friends who accidentally (or not) committed murder. Their target was the one they branded a moonman, who suffered from a disfiguring disease. The characters in that story were afflicted by the irrational fear of the Other. Having these characters undergo such disorders and diseases enables me to come to terms with some of the things I fear.

What are some of your favorite stories or books that deal with real or imagined illnesses?

Kim Parko’s Cure All from Caketrain Books has interesting stories about mostly made-up illnesses. And one of the most unforgettable stories I’ve read about illnesses is David B. Silva’s psychological horror story “The Calling.” It is about a man who keeps hearing a strange whistling sound in the house where he tends to his dying mother, who was outfitted with a colostomy bag. I have had nightmares about that story. It is an unpleasant reminder of the various indignities, on top of physical pain and emotional torment, suffered by terminal disease patients.

One thing I think readers will find really engaging about Age of Blight is that you work with many different POVs and styles. Do you have a default POV that you usually write your stories in? How do you know when the chosen point of view is the right one for the story?

I love writing and reading stories and poems that use the second-person narrative mode. I feel that the second-person POV tells stories closely enough to remain detached. I consider first how I’m supposed to frame whatever it is that I wanted to say in a story. Then I decide on which POV to use. For example, in my retelling of Harry Harlow’s sordid exploits in “The Wire Mother” in Age of Blight, I don’t think that story would work when told in third person.

What’s the most recent book you’ve read and really enjoyed? Why?

My Cruel Invention (Meerkat Press, 2015), a poetry anthology edited by Bernadette Geyer, is one of the most intelligently curated themed anthologies I’ve read recently. The poems were about inventions, both real and imagined. My absolute favorites were the poems about the ethical underpinnings of certain inventions and technological advances, the most notable being Janet McNally’s “Direct Current,” a poem that talks about the hypocrisy in how these are remembered in history—puppies that were electrocuted by Thomas Edison and an abused elephant deemed a “murderer” when she finally snapped and killed a man who threw a lit cigarette into her mouth. This is just one of the many thought-provoking poems in My Cruel Invention, which I really really enjoyed. Why? We tend to tell the same story over and over, the same story about wanting some sort of recourse, redemption, resolution. What’s left after the retelling is a great poem.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.