by Pilar DiPietro

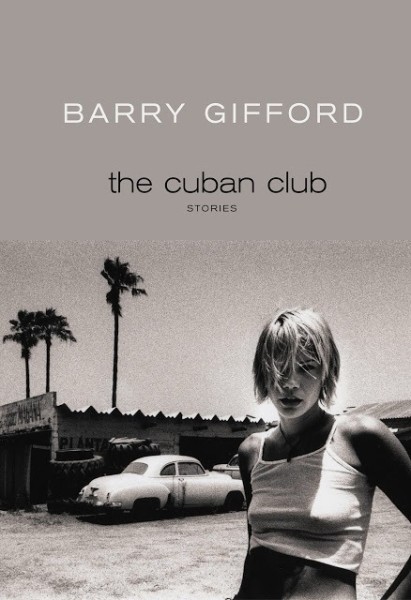

Often we think of life in the 1950s as one of wistful innocence and familial ease. We may even term it “the Good Old Days.” Barry Gifford’s The Cuban Club (Seven Stories Press, October 2017), a collection of sixty-seven related stories, pushes back on these notions of nostalgia with the remembrances of Roy. Roy is a first-generation American, Chicagoan by way of Miami in his youth. Trying to make his way through the snarls of puberty, Roy unties the knots of race, marriage and fidelity, death, sex and love, violence, grief, loss, and parent-child relationships.

In the snippets that make up Roy’s memories, the reader gains an understanding of the changing parental, domestic, family and moral roles that were sweeping through America in the 1950s and early 1960s and the effects these changes were having on the next generation. Through Roy’s eyes the reader is given insight: not only the fascinations of youth but the reflections of a changing time. Throughout the stories Gifford maintains Roy’s delightful innocence in the foreground, his youthful misunderstandings often tumbling out of his mouth, though alluding to the real situation that runs deeper, and often darker, behind.

Uniquely, and indeed digitally friendly, Gifford allows the reader to open to any of his stories and feel like it may have been exactly where you left off. There is no need to read this collection in any particular order. Roy’s stories, each approximately three pages long, identify the age at which Roy is recording them. This grounding is helpful in seeing Roy’s progression, his bildungsroman, as he grapples with situations that, perhaps, no boy should be aware of. I recommend mixing up your reading order and enjoying the stories outside linear time.

The book does contain some violence. While uncomfortable at times, it is palatable. Roy’s father, a mid-level racketeer with mob affiliations, is on one hand protective of his son, and yet his fatherly advice frequently verges on the morally hypocritical. For example, after Roy learns that Mean Well Benny’s cut-throated corpse was found in an alley garbage can, Roy’s father says, “Some men’s lives don’t amount to much, son. They get on the wrong road and don’t ever get back on the straight and narrow.” Luckily, Roy’s pops gives more solid lessons: “I’m sorry to say, Roy, I believe in the existence of evil. Hitler, for example, was an evil man who had the ability to inspire and manipulate people into committing the most gruesome acts of villainy.” Although Roy’s father is ambiguously depicted as being involved with illegal enterprises, his pronouncements, along with Pops’, are sound enough to aid in the formation of Roy’s ethical balance. Gifford writes in a manner allowing for reader understanding without author subjectivity.

Roy’s mother, an aging ex-model, ricochets from one boyfriend to another and often leaves Roy in the care of others while she jet-sets in search of love and adventure. By thirty-four she is quite jaded and has been married three times. The conversations between her and her equally disenchanted friend, Kay, are often overheard by Roy who is left to make his own conclusions and seldom have little to do with the actual meaning of the quips. For example, after Kay, speaking of orgasms, tells Roy that his mom has had an epiphany, Roy asks, “Do you have to be a Catholic to have one?” to which Kay answers, “No, Roy, but it probably helps.”

Johnny Murphy, Roy’s friend, teaches Roy about the underside of life, a seedy underbelly seems taken for granted by the characters. When Roy and Johnny decide to play detective after the grisly murder of a young woman is discovered, Johnny off-handedly states, “He raped the girl, strangled her—or maybe, if he was a real pervert, strangled her before raping her.” The eleven-year-old boys go to the crime scene to search for clues and Johnny deduces: “The killer’s a rich guy who lives in a fancy apartment around here, on Lake Shore or Marine Drive.” Indeed, the killer was found to be “a 42-year-old bachelor named Leonard Danzig, an architect,” who had determined the girl was the sister of Jesus Christ and “felt it was his duty to abort what he described as an immoral lineage.” After the killer was captured and committed, Roy asks his mother what she thinks. She tells her son, “You can’t execute all of the sick people in the world, Roy. There are too many. Once you start doing that it would never stop.” Roy then asks if she thinks the world would be better without the killer in it. Gifford’s next lines are typical of his style: “Roy’s mother, who had already been divorced twice and had a third marriage annulled, said, ‘Him and a few other men I can name.’”

Readers will enjoy Roy’s adventures, if not contemplate Gifford’s true intentions. The tales, often having many meanings, are a wonderful mix of ingredients that enfold a boy’s journey of adolescence in urban 1950s America. The result of the collection is a layered spiced cake with each of Roy’s episodes demanding the reader’s introspection of their own identity and values.

The Cuban Club is available from Seven Stories Press. Or from Amazon.

___________________________

Pilar DiPietro is a fan of crossing lines, changing lanes and the outside of boxes. She is currently a MA candidate in Rhetoric and Composition at Winthrop University in Rock Hill, SC.

Pilar DiPietro is a fan of crossing lines, changing lanes and the outside of boxes. She is currently a MA candidate in Rhetoric and Composition at Winthrop University in Rock Hill, SC.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.

The core workshop of SmokeLong Fitness is all in writing, so you can take part from anywhere at anytime. We are excited about creating a supportive, consistent and structured environment for flash writers to work on their craft in a community. We are thrilled and proud to say that our workshop participants have won, placed, or been listed in every major flash competition. Community works.